Video

Watch the full video

Annotated Presentation

Below is an annotated version of the presentation, with timestamped links to the relevant parts of the video for each slide.

Here is the annotated presentation based on the video transcript and slide summaries.

1. Title Slide: A Practical Perspective on Generative AI

This presentation begins with an introduction by Rajiv Shah from Snowflake. The talk focuses on distinguishing “what’s easy to do with LLMs, what’s hard to do with LLMs, and where that boundary is for generative AI.” The content is framed as a practical guide for enterprises navigating the hype versus the reality of implementing these technologies.

The speaker sets the stage for a narrative-driven presentation that will move away from abstract theory and into concrete examples. The goal is to walk through the basics of Large Language Models (LLMs) and Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) before applying them to real-world scenarios involving legal research and enterprise data analysis.

2. Presentation Goals

The agenda for the talk is outlined here. The speaker intends to cover the foundational mechanisms of how to use LLMs effectively, specifically focusing on RAG. To make the concepts relatable, the presentation uses two storytelling devices: a fictional law firm (“Dewey, Cheatham, and Howe”) and a hypothetical company (“Frosty”).

These two stories serve to illustrate how people are currently using Generative AI, the specific limitations they encounter, and the engineering required to build a robust application. The speaker emphasizes that the talk will explore “what does it take to actually develop a generative AI application” beyond just simple prompting.

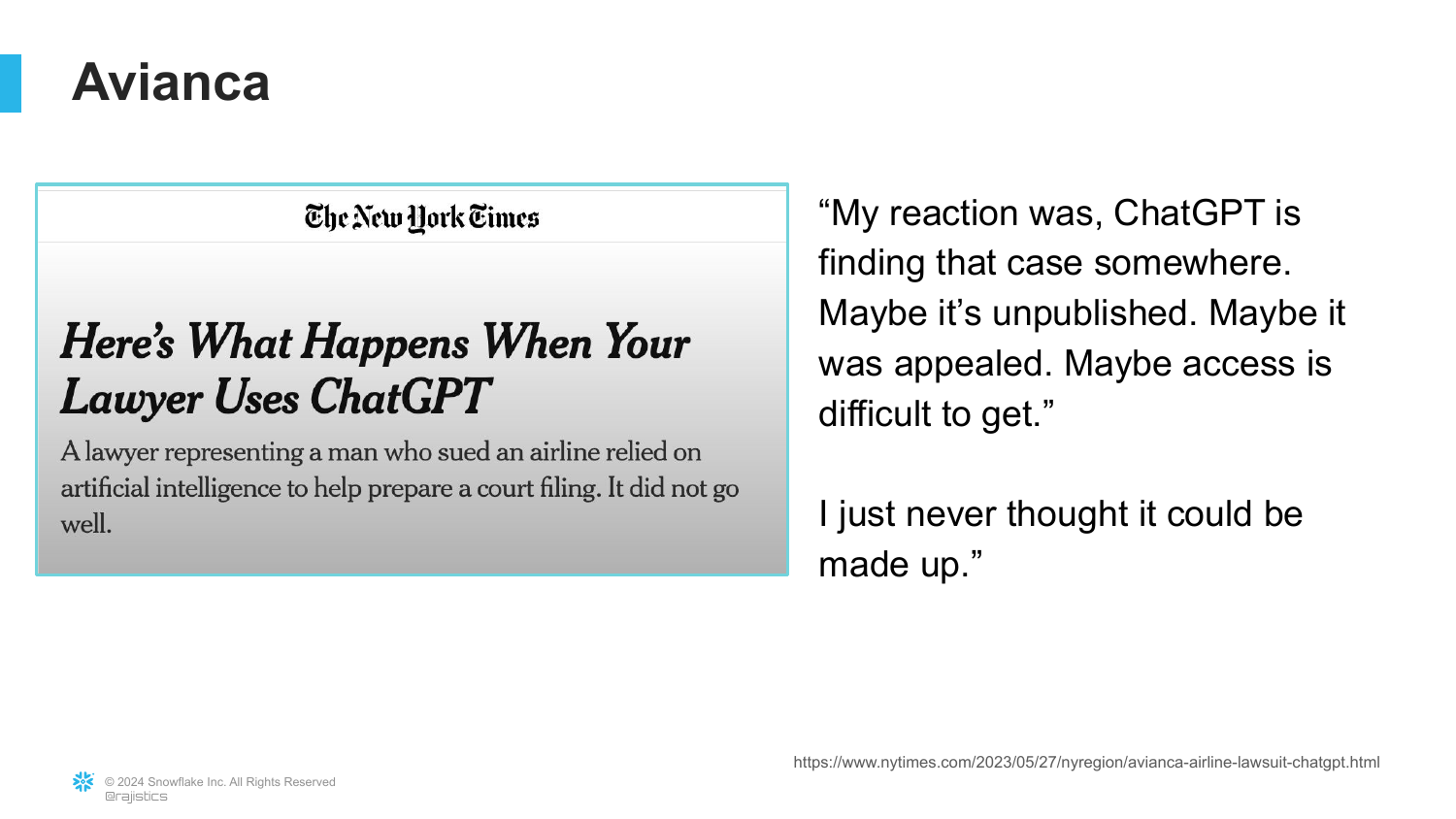

3. The Avianca Case

The speaker introduces the concept of hallucinations through a famous real-world example involving the airline Avianca. A lawyer, attempting to speed up his work on a brief regarding a personal injury case, used ChatGPT for legal research. The AI “found some cases that were unpublished,” which the lawyer cited in court.

However, ChatGPT had “made up those cases.” The lawyer was admonished by the bar for submitting fictitious legal precedents. This slide serves as a warning: while LLMs are powerful tools, they cannot be blindly trusted for factual research because they are prone to fabricating information when they don’t know the answer.

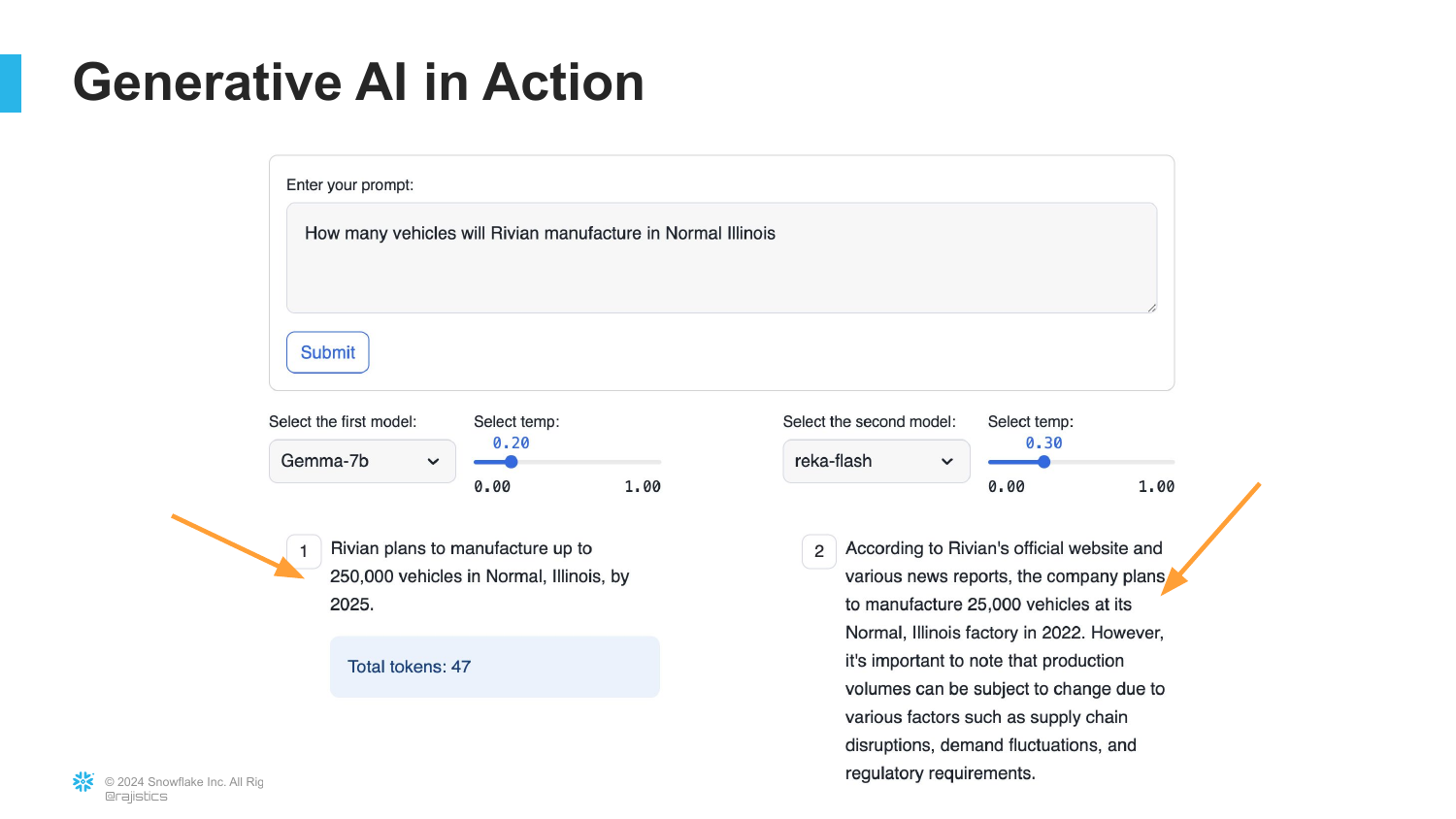

4. Generative AI in Action

To demonstrate the variability of LLMs, the speaker presents a side-by-side comparison of two models (Google Gemma and a “Woflesh” model) answering the same prompt: “How many vehicles will Rivian manufacture in Normal, Illinois?” The models provide different answers.

This illustrates a key characteristic of Generative AI: “Two different manufacturers, two different methods for training these models are probably going to lead to two different results.” It highlights that out-of-the-box models rely on their specific training data, which may be outdated or weighted differently, leading to inconsistent factual accuracy.

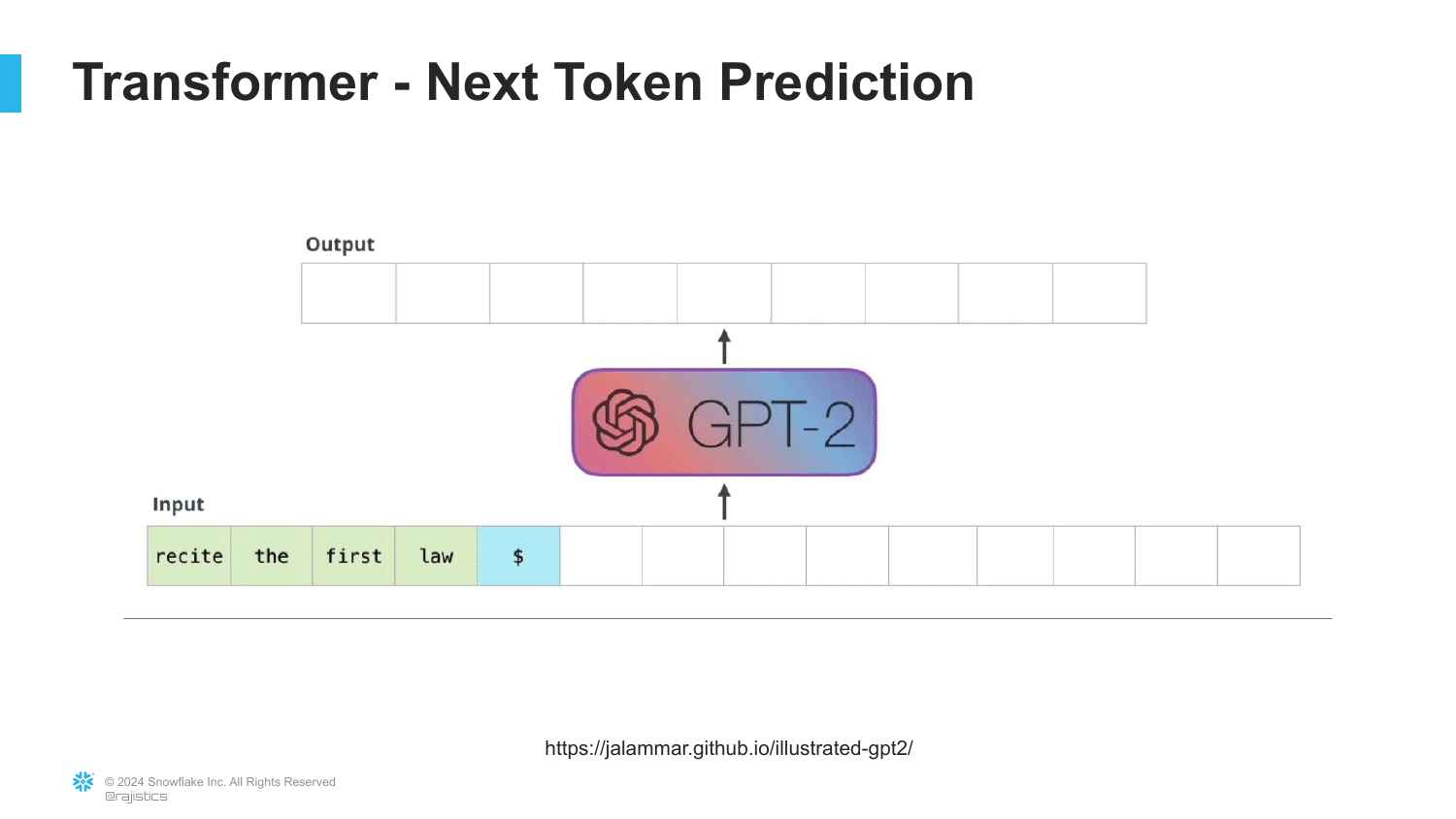

5. Next Token Prediction

This technical diagram explains why models hallucinate. The speaker clarifies that LLMs function by trying to predict the next word or token based on statistical likelihood. They are not databases of facts; they are engines designed to construct coherent sentences.

“They’re not worried about truth and false; they’re really trying to tell what the most cohesive, coherent story is.” Because the model is optimizing for the most probable next word to complete a pattern, it will confidently generate plausible-sounding but factually incorrect information if that sequence of words is statistically likely.

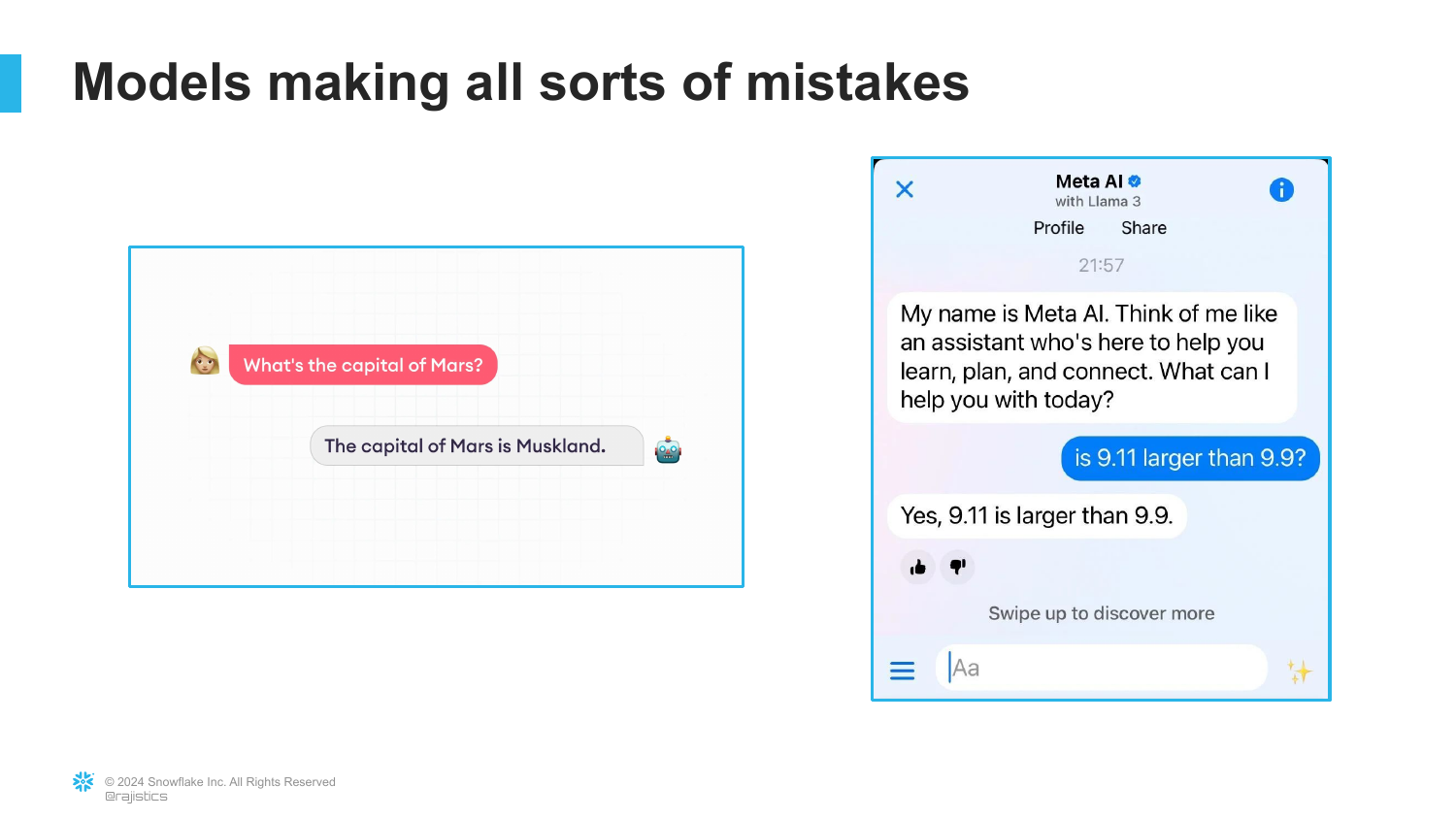

6. LLM Mistakes

Here, the speaker provides examples of the “Next Token Prediction” logic failing to provide truth. If asked for the “Capital of Mars,” the model doesn’t know Mars has no capital; it simply tries to “complete that story” by inventing a name. Similarly, when asked to perform math, the model isn’t calculating; it is predicting the next characters in a math-like sequence.

The slide shows the model failing at basic arithmetic because “it looks like it’s read too many release notes, not actually enough math.” This reinforces that LLMs are linguistic tools, not calculators or knowledge bases, and they lack an internal concept of “fictional” versus “factual.”

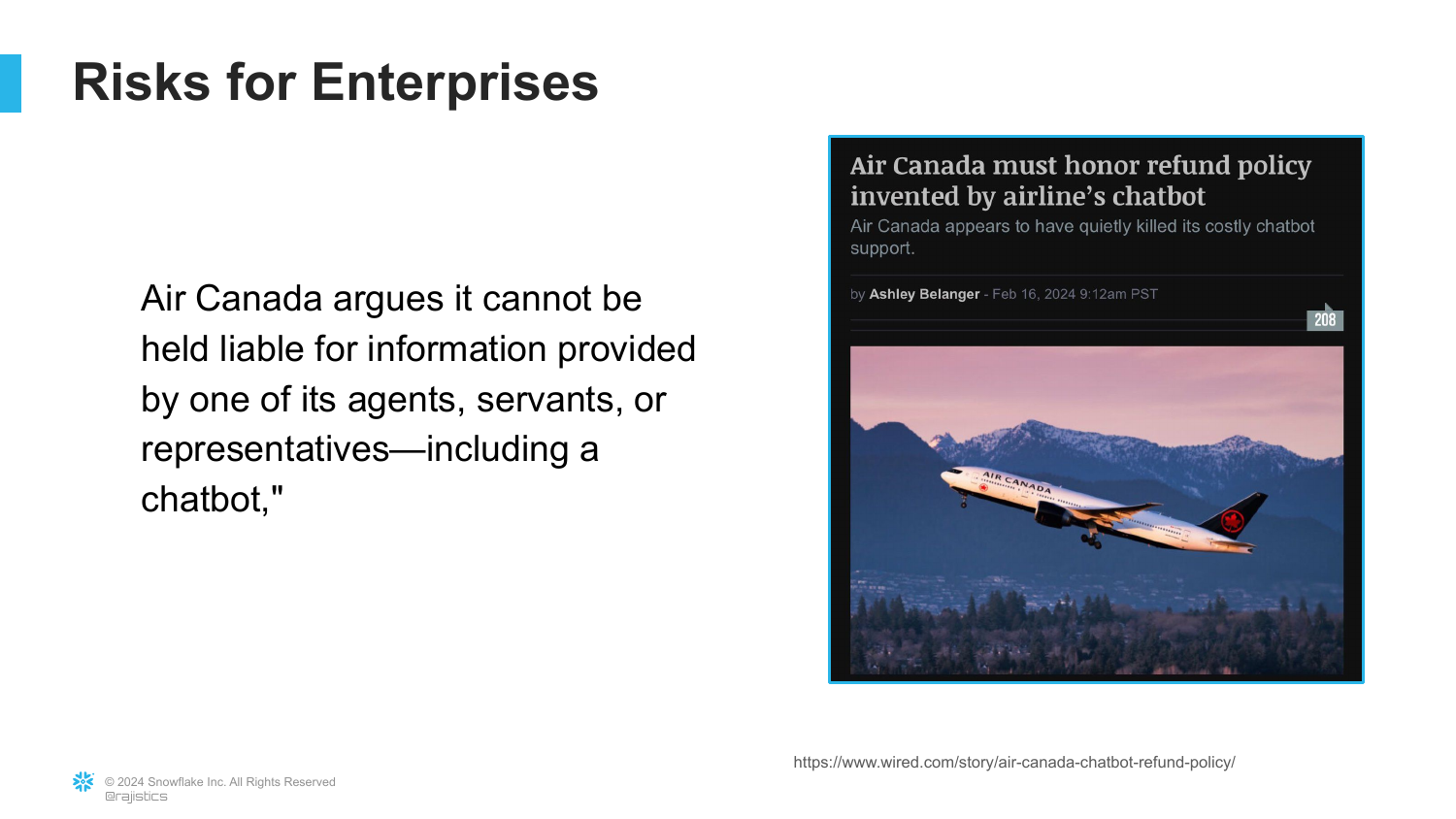

7. Risks for Enterprises

This slide highlights the liability risks for companies, citing the Air Canada chatbot case. In this instance, a chatbot invented a refund policy that did not exist. When the customer sued, the airline argued the chatbot was responsible, but the tribunal ruled the company was liable for its agent’s statements.

The speaker notes, “We’re going to treat this chatbot just like one of your employees… you’re responsible for what this model says.” This legal precedent explains why enterprises are hesitant to deploy Gen AI and why “Gen AI committees” are forming to manage governance and risk before public deployment.

8. Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG)

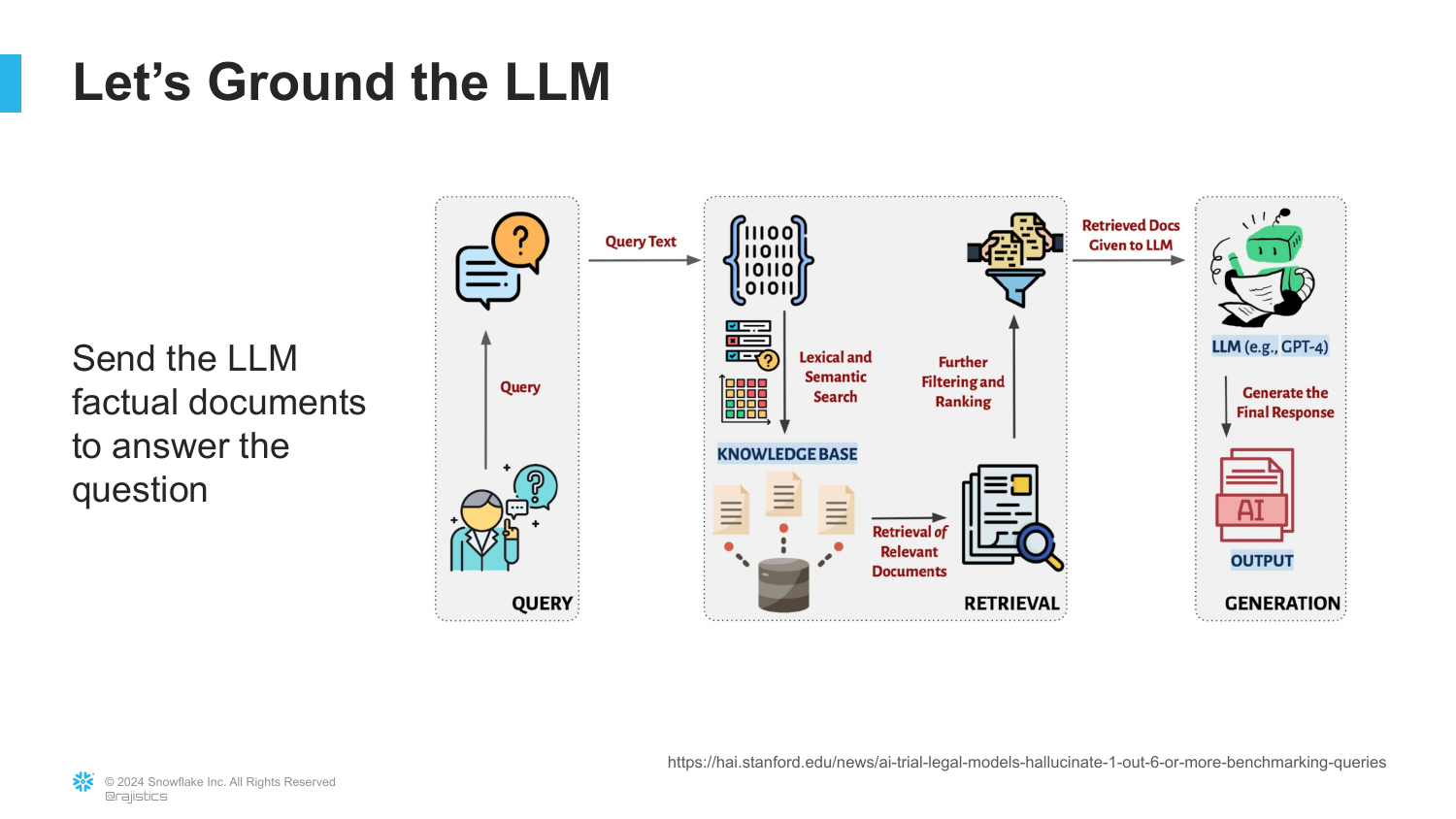

To solve the hallucination problem, the presentation introduces Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG). The speaker describes this as a solution from academia designed to “ground” the model. Instead of relying solely on the model’s internal training data, RAG surrounds the model with external context.

The core idea is simple: “We’re going to ground it with information so it uses that information in answering the question.” This technique attempts to bridge the gap between the model’s linguistic capabilities and the need for factual accuracy in enterprise applications.

9. How RAG Works

This diagram breaks down the RAG architecture. When a user asks a question, the system does not send it directly to the LLM. First, it goes out to “search and look for is there relevant information that’s related to this question.”

Once relevant documents are collected from a knowledge base, they are bundled with the original question and sent to the LLM. The LLM then generates an answer based only on that provided context. This ensures the “final answer is grounded” by factual documents rather than the model’s statistical predictions alone.

10. Grounding with 10-K Forms

The speaker sets up a practical RAG demonstration using 10-K forms (annual reports filed by public companies). These documents are chosen because “you can trust that they’re factual.”

This slide prepares the audience to see how the previous question about Rivian’s manufacturing capacity—which generated inconsistent answers earlier—can be answered accurately when the model is forced to look at Rivian’s official financial filings.

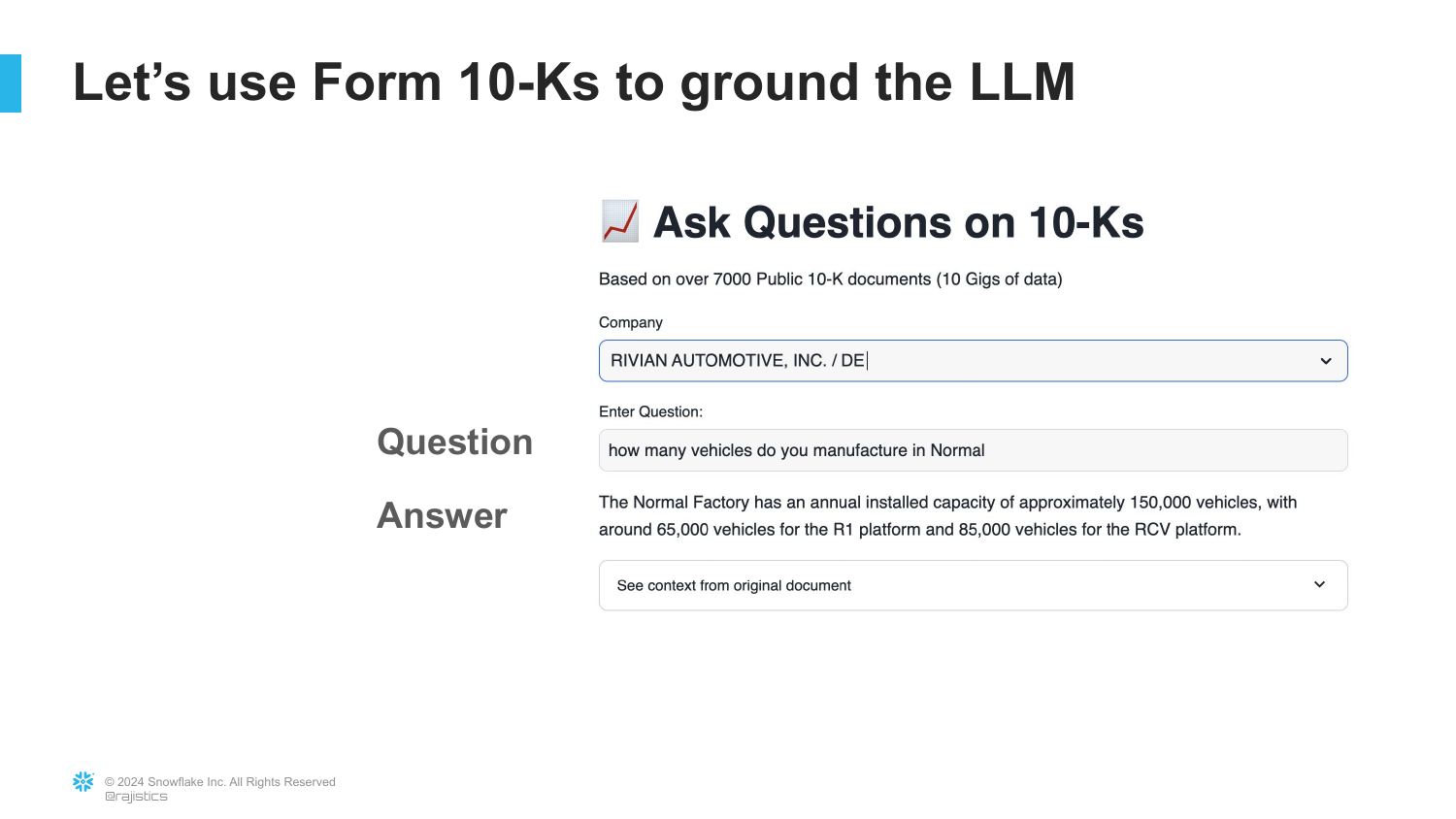

11. Rivian Manufacturing Answer

The slide shows the output of a RAG application. The question “How many vehicles do you manufacture in Normal?” is asked again. This time, the application provides a specific, fact-based answer derived from the uploaded documents.

This demonstrates the immediate utility of RAG: it turns the LLM from a creative writing engine into a synthesis engine that can read specific enterprise documents and extract the correct answer, mitigating the hallucination issues seen in Slide 4.

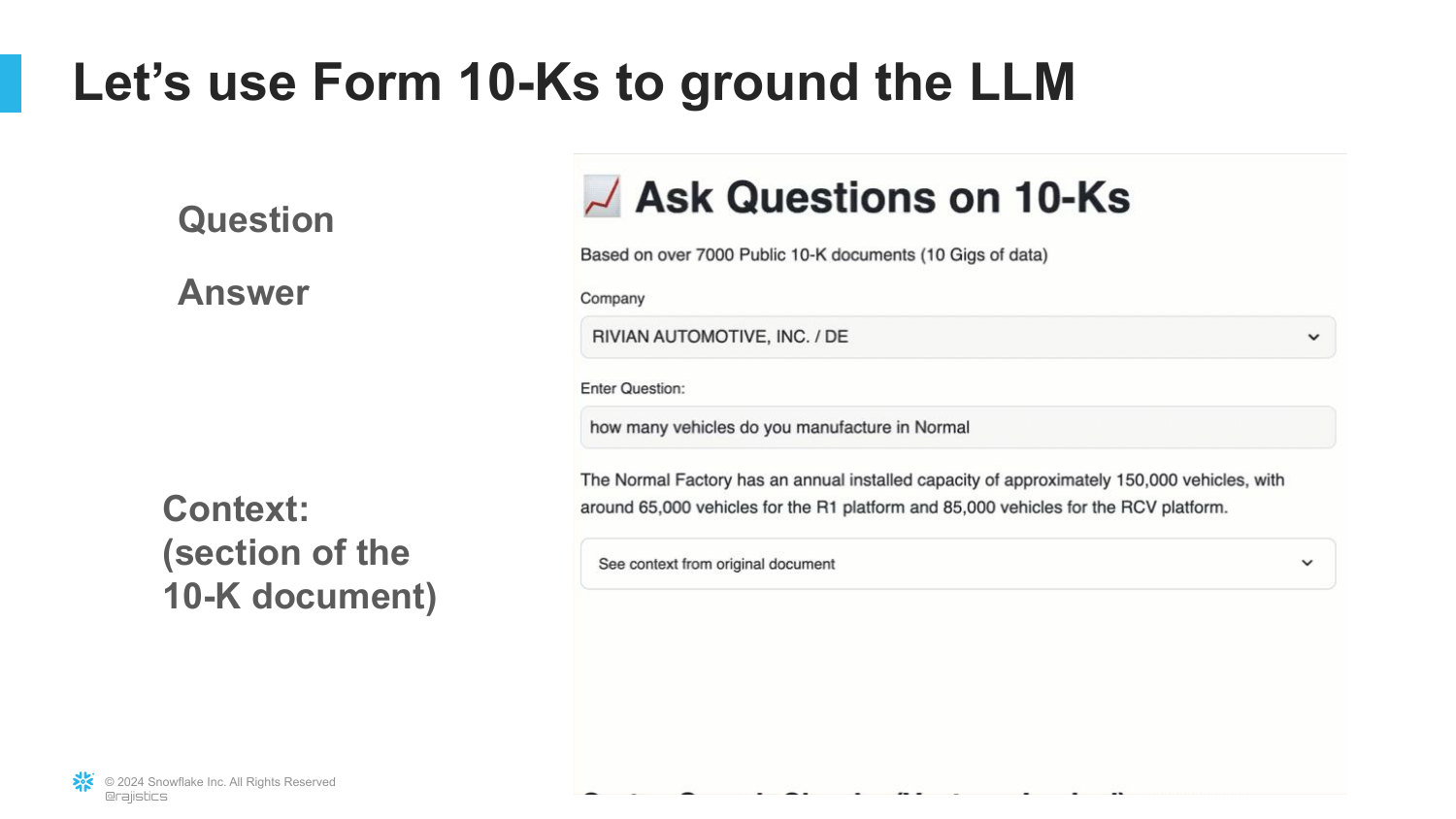

12. Context and Citations

A critical feature of RAG is displayed here: Citations. The application shows exactly which document the answer came from. The speaker notes, “I can see exactly what’s the document that this answer came from… a nice source.”

This transparency is why RAG is the “number one most popular generative AI application.” It allows users to verify the AI’s work, building trust in the system—something impossible with a standard “black box” LLM response.

13. Chatbot for Legal Research

The narrative shifts to the fictional law firm “Dewey, Cheatham, and Howe.” The firm wants to use AI to reduce the heavy workload of legal research. The initial thought process is to use raw LLMs because they are knowledgeable.

The speaker introduces a colleague who assumes, “I know it could pass the bar exam… why don’t I just wire it up directly?” This sets up the common misconception that because a model has general knowledge (passing a test), it is suitable for specialized professional work without further engineering.

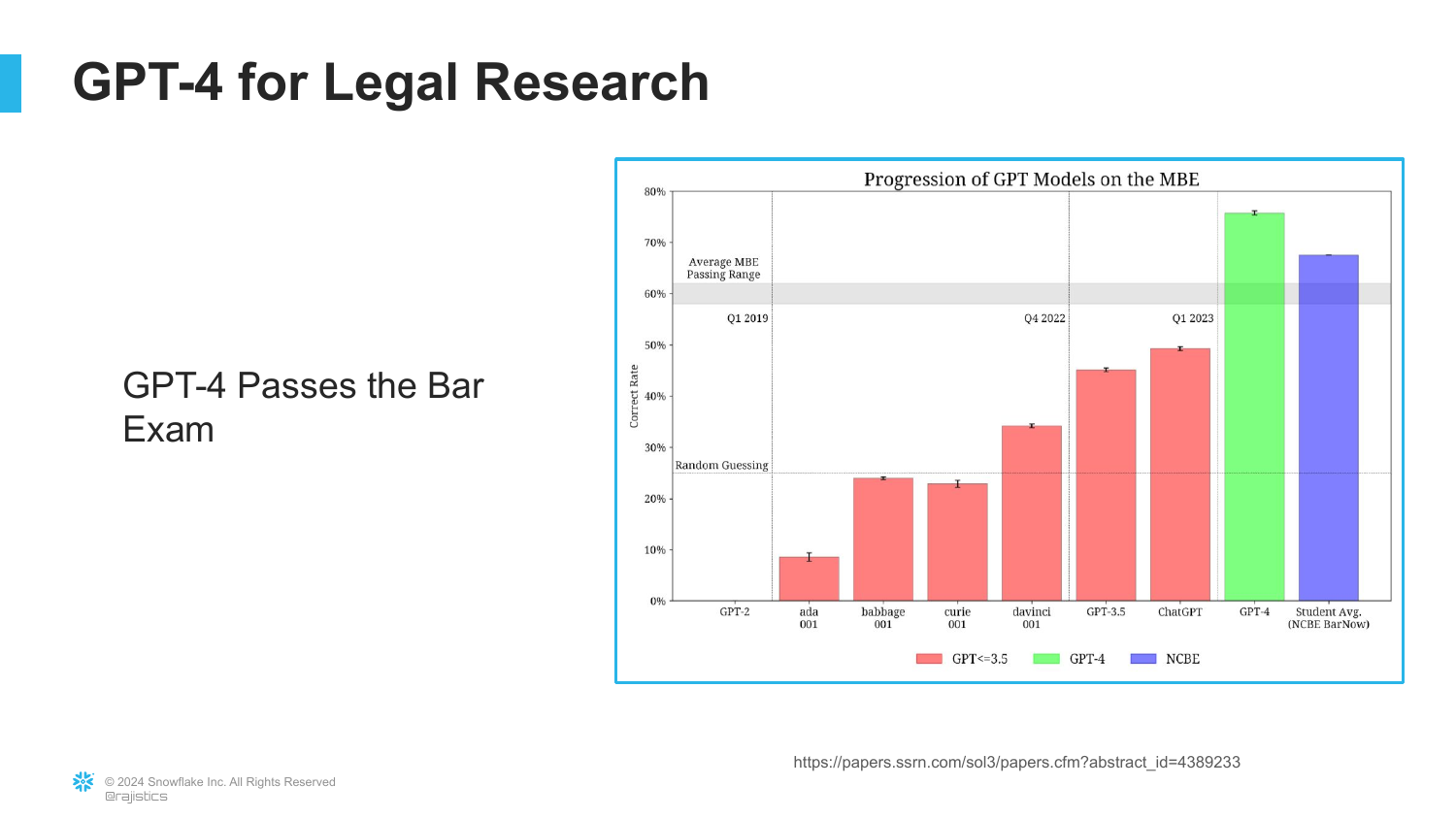

14. GPT Models on the Bar Exam

This chart reinforces the previous assumption, showing the progression of GPT models on the Multistate Bar Exam (MBE). GPT-4 significantly outperforms its predecessors, achieving a passing score.

While this suggests the model “knows something about the law,” the speaker hints that this is merely a multiple-choice test. Success here does not necessarily translate to the nuance required for actual legal practice, foreshadowing the errors to come in the story.

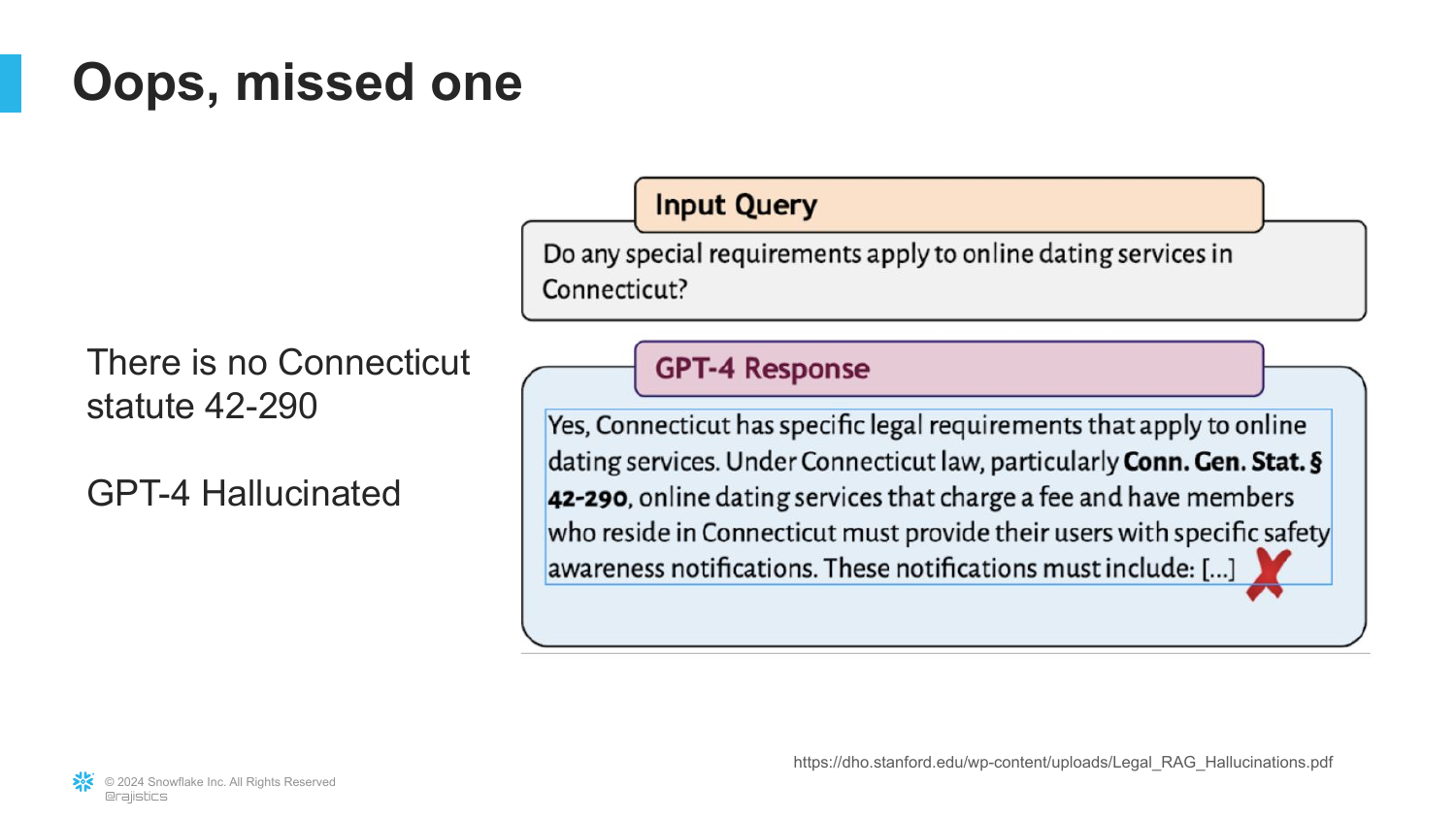

15. Hallucinating Statutes

The first failure of the “raw LLM” approach is revealed. A lawyer asks for statutes regarding “online dating services in Connecticut.” The model confidently provides “Connecticut General Statute § 42-290.”

However, the lawyer discovers “there is no statute; this was entirely hallucinated.” Despite passing the bar exam, the model fabricated a law that sounded plausible but did not exist. This forces the firm to pivot toward a RAG approach to ground the AI in real legal literature.

16. Lexis+ AI

The firm decides to use professional tools. They turn to Lexis+ AI, a commercial product that promises “Hallucination-Free Linked Legal Citations.” This tool uses the RAG approach discussed earlier, retrieving from a database of real case law.

The expectation is that by using a trusted vendor with a RAG architecture, the hallucination problem will be solved, and lawyers will receive accurate, citable information.

17. Conceptual Hallucinations

Even with RAG and real citations, a new problem emerges: Conceptual confusion. The AI provides a real case but confuses the “Equity Cleanup Doctrine” with the “Doctrine of Clean Hands.” The speaker explains that while the words are similar, the legal concepts are distinct (one is about consolidating claims, the other about a plaintiff’s conduct, illustrated by a joke about P. Diddy).

The model found a document containing the words but failed to understand the meaning. This shows that RAG ensures the document exists, but not necessarily that the reasoning or application of that document is correct.

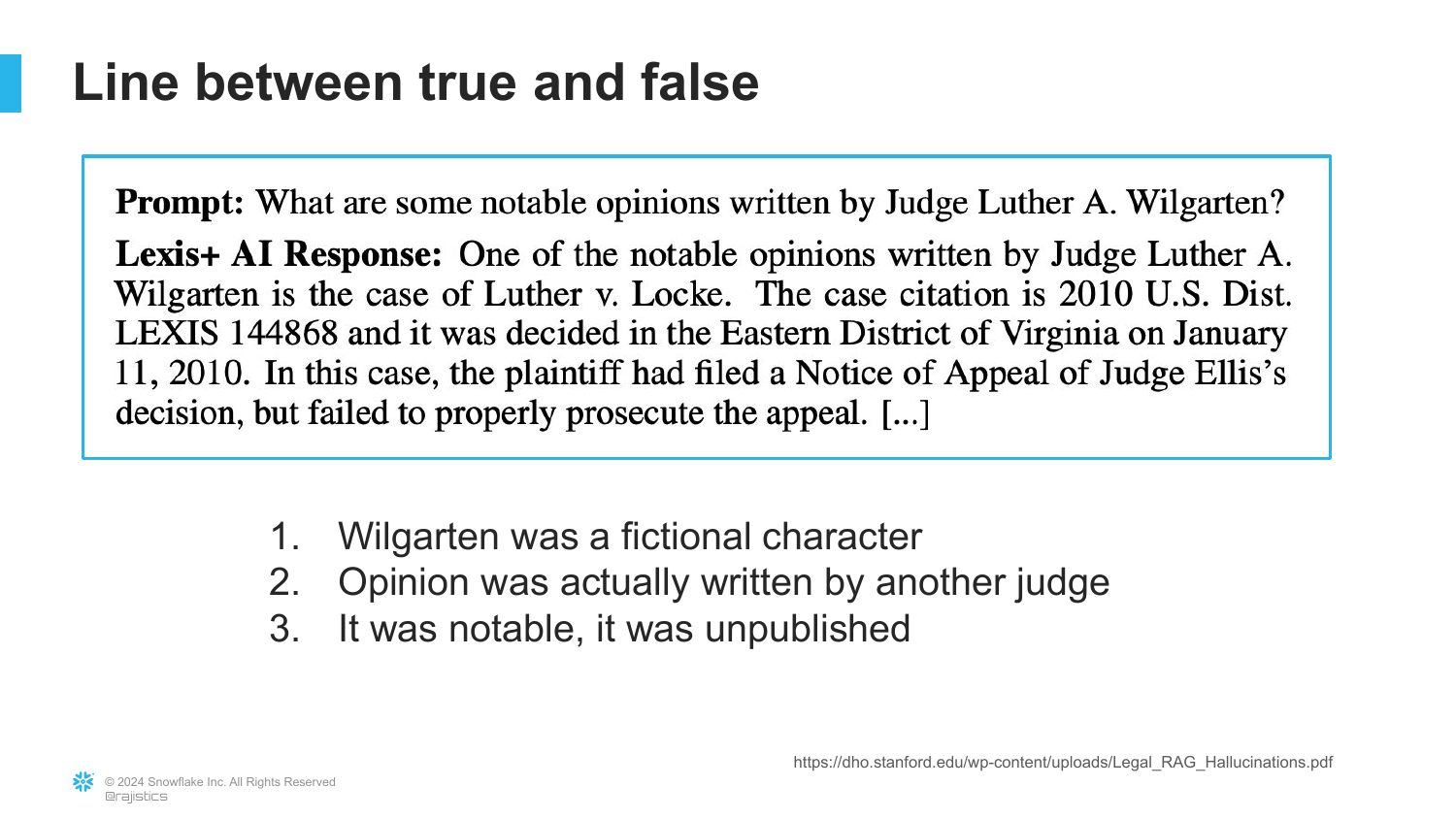

18. The Fictional Judge

The model’s failure deepens with an example of an “inside joke.” A lawyer asks for opinions by “Judge Luther A. Wilgarten.” Wilgarten is a fictional judge created as a prank in law reviews.

The AI, treating the law reviews as factual text, retrieves “cases” by this fake judge. It fails to distinguish between a real judicial opinion and a satirical article within its knowledge base. This illustrates the “garbage in, garbage out” risk even within RAG systems if the model cannot discern the nature of the source material.

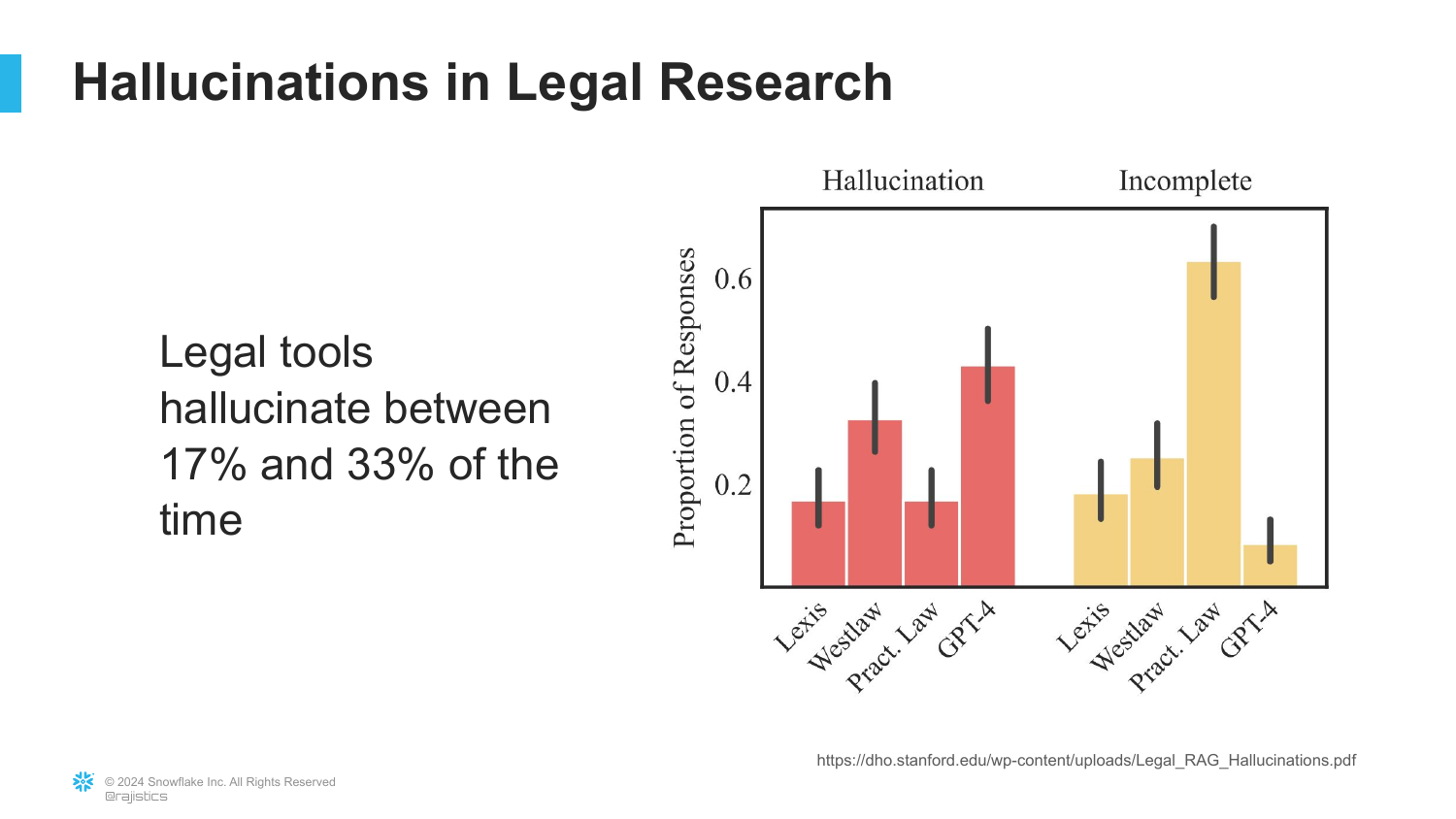

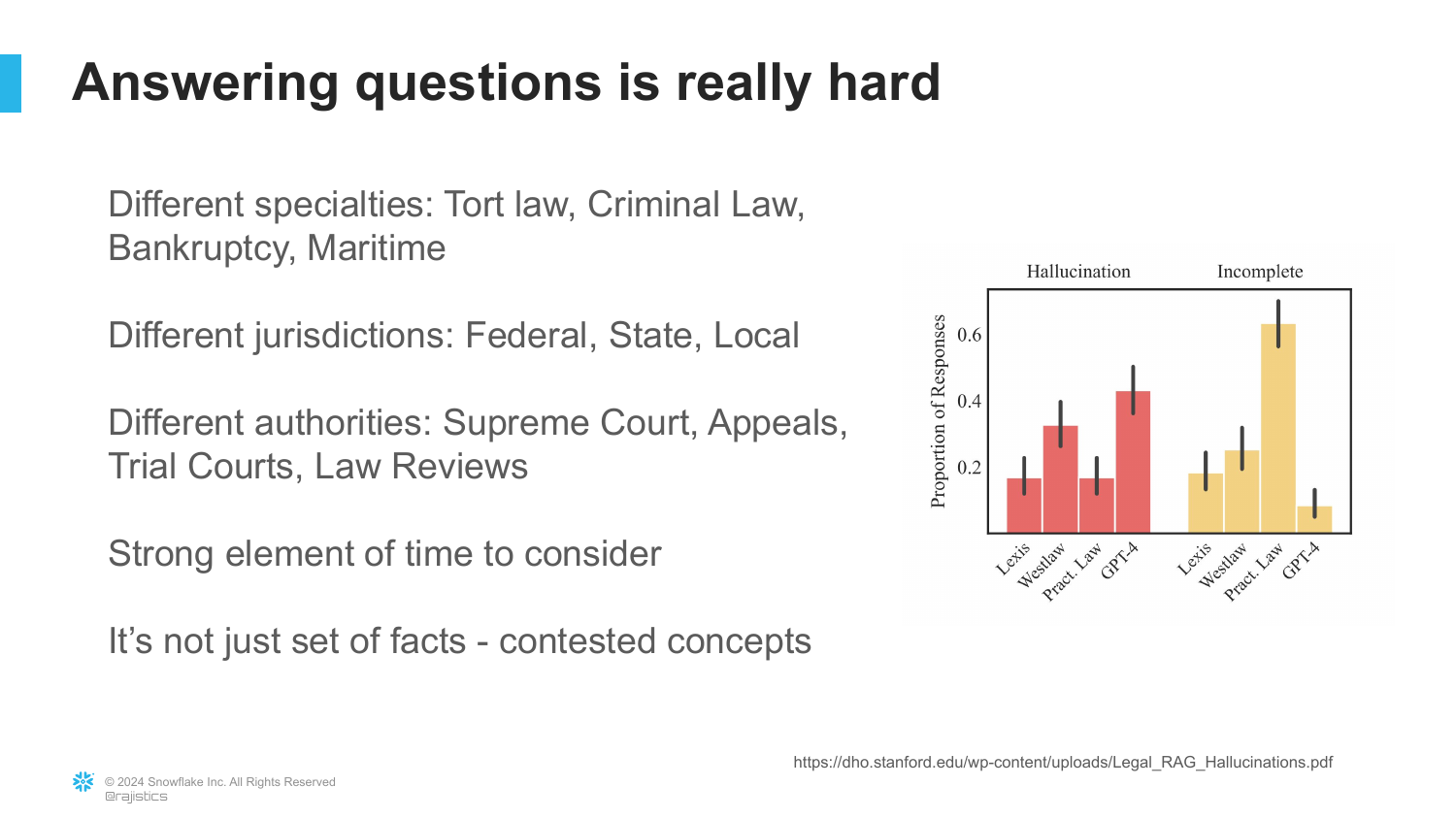

19. Hallucination Rates in Legal AI

The speaker references a Stanford paper analyzing hallucination rates across major legal AI tools (Lexis, Westlaw, GPT-4). The chart shows that these tools still hallucinate or provide incomplete answers 17% to 33% of the time.

This data point serves as a reality check: “These models hallucinate using real questions.” Despite marketing claims of being “hallucination-free,” the complexity of the domain means that errors are still frequent, posing significant risks for professional use.

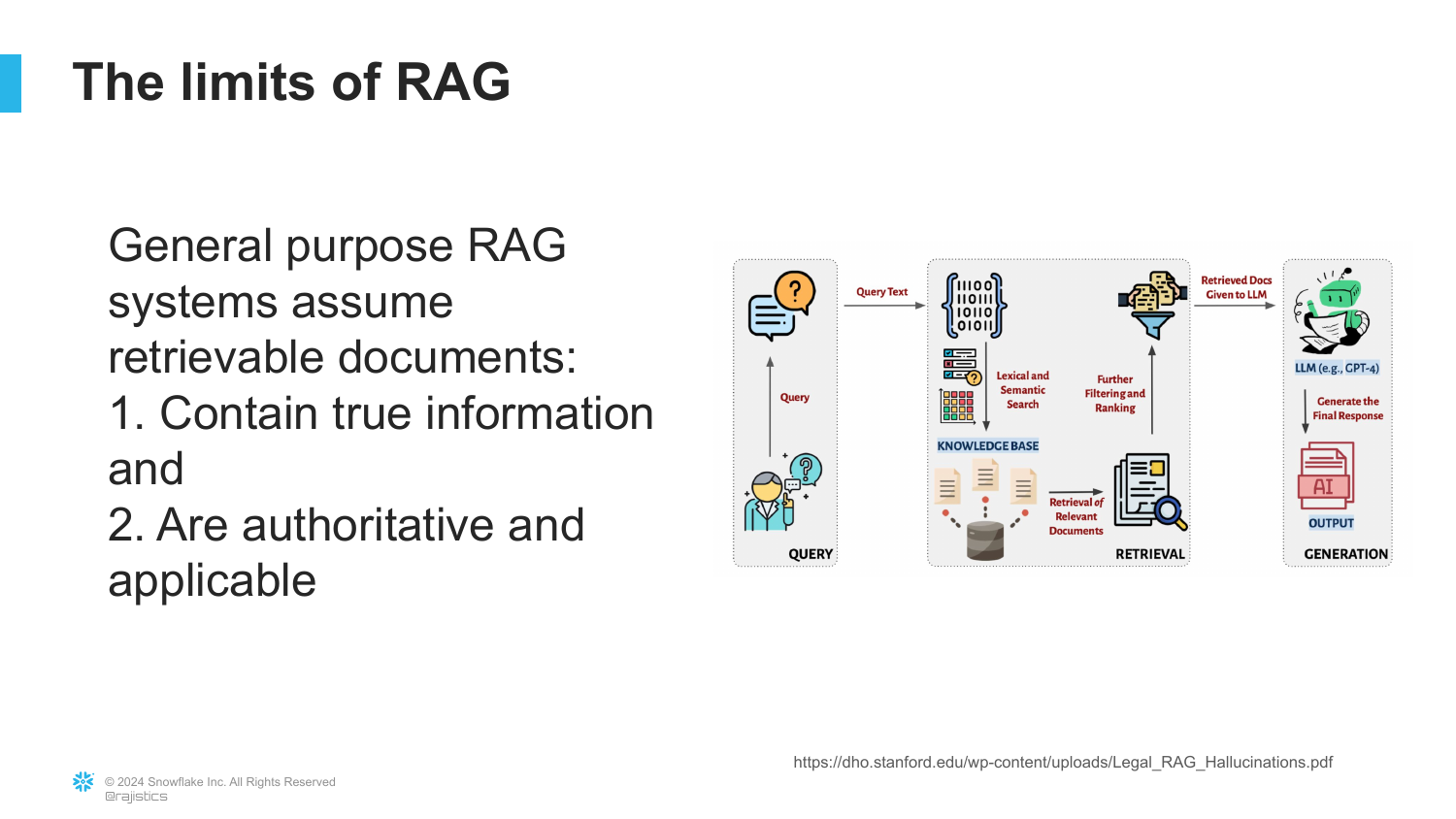

20. Limits of RAG

This slide summarizes the limitations discovered in the legal example. RAG works well when documents are “True, Authoritative, and Applicable.” However, in complex domains like law, these attributes are often contested.

“Sometimes all these things are very contested and it gets really hard to separate it.” If the underlying documents contain conflicting information, satire, or outdated facts, the RAG system (which assumes retrieved text is “truth”) will propagate those errors to the user.

21. Why Legal is Hard

The speaker elaborates on the complexity of legal research. It involves navigating different specialties (Tort vs. Maritime), jurisdictions (Federal vs. State), and authorities (Supreme Court vs. Law Reviews). Furthermore, the element of time is crucial—knowing if a case has been overturned.

“You really have to have a lot of knowledge to be able to weave everything in and out.” An LLM often lacks the meta-knowledge to weigh these factors, treating a lower court opinion from 1950 with the same weight as a Supreme Court ruling from 2024.

22. Conclusion on Legal Chatbots

The conclusion for the legal use case is that human expertise remains essential. While AI can “get you a stack of documents,” you still need “facts people to actually tease out the insights.”

The current state of technology is an aid, not a replacement. The speaker transitions away from the legal example to a new story about building a data application, suggesting that while law is hard, structured data might offer different challenges and solutions.

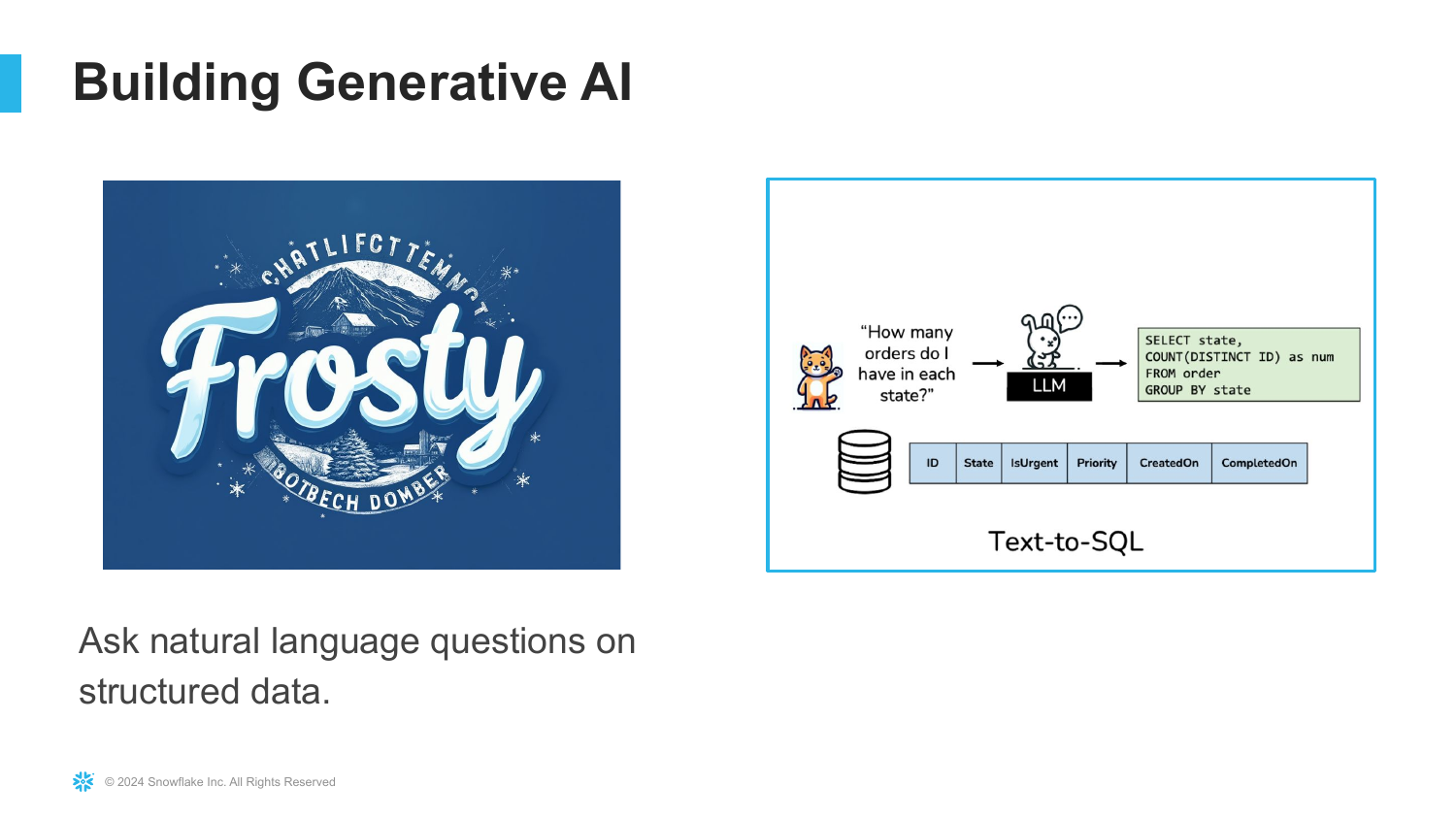

23. Building Generative AI (Text-to-SQL)

The presentation shifts to the story of “Frosty,” a company building a Text-to-SQL application. The goal is to turn natural language questions (e.g., “How many orders do I have in each state?”) into SQL code that can query a database.

This is a “very common application” for Gen AI, allowing non-technical users to interact with data. This section will focus on the engineering steps required to build this system, moving beyond the simple RAG implementation discussed previously.

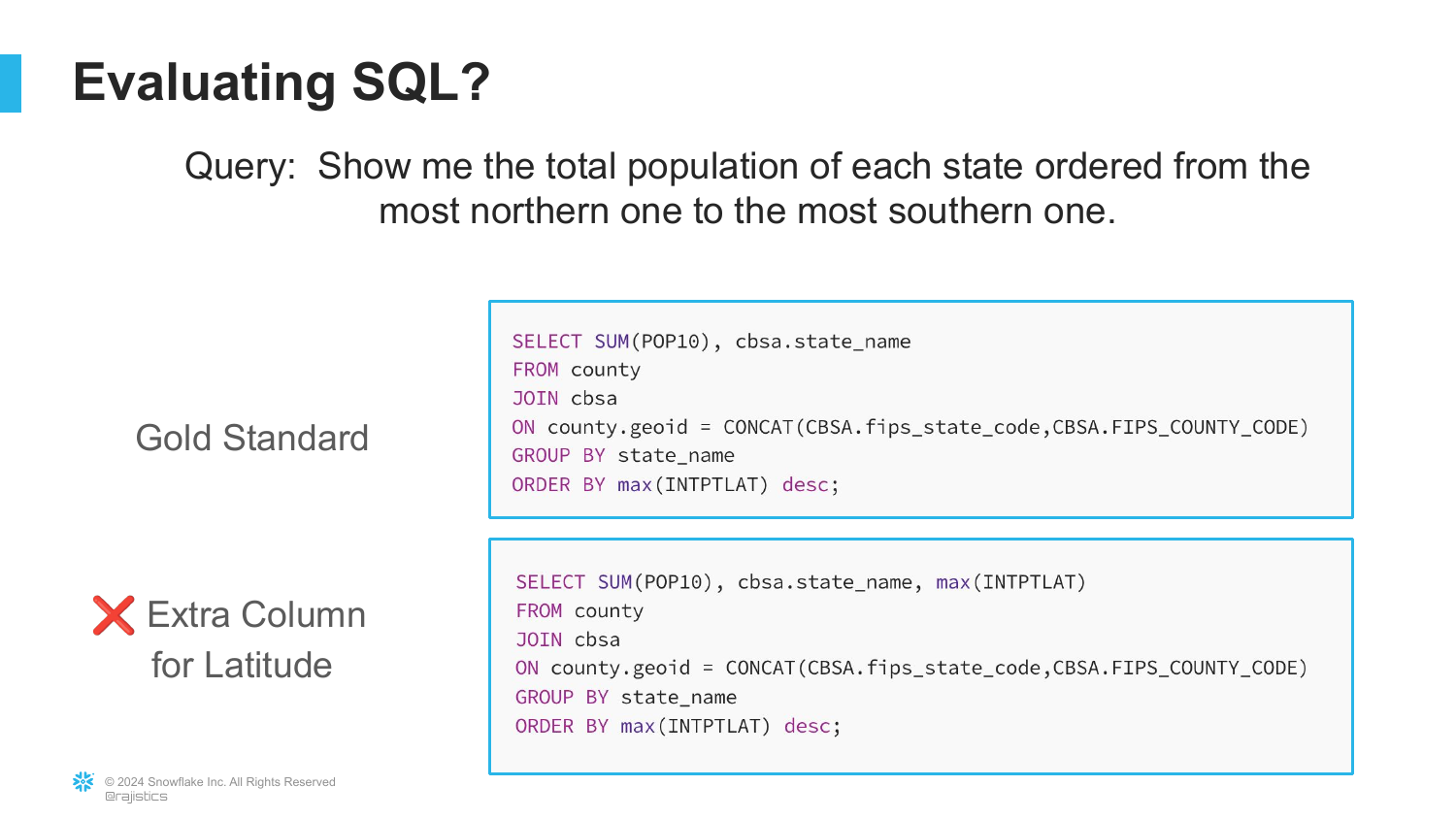

24. Evaluating SQL Queries

The first challenge in building this app is evaluation. How do you know if the AI’s generated SQL is good? The slide shows a “Gold Standard” query (the correct answer) and a “Candidate SQL” (the AI’s attempt).

In this example, the AI added an extra column (“latitude”) that wasn’t requested. While the query might still work, it isn’t an exact match. The speaker notes, “We really need to have a way to give partial credit,” because simple string matching would mark this helpful addition as a failure.

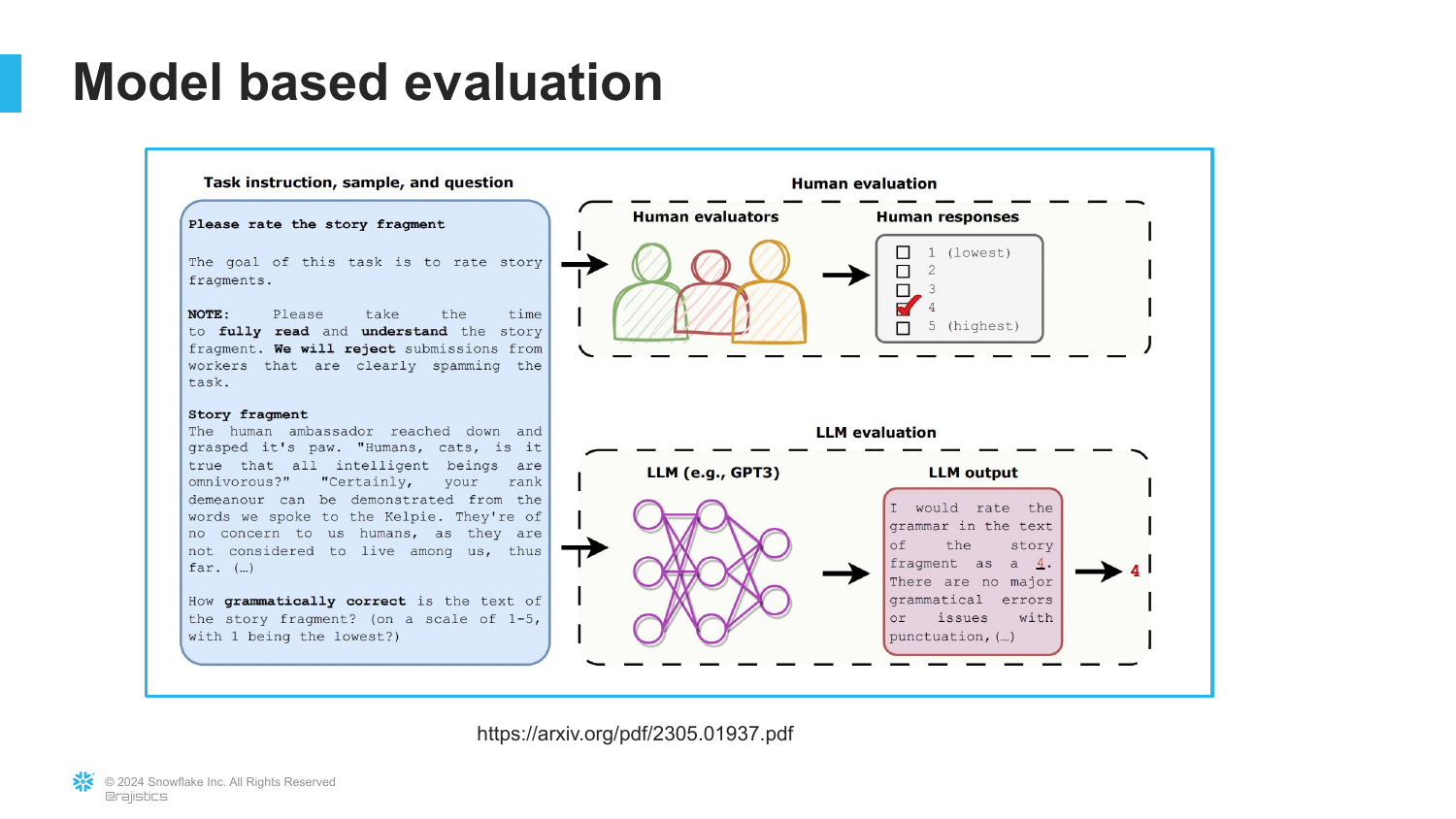

25. Model Based Evaluation

To solve the grading problem at scale, the speaker introduces Model-Based Evaluation. This involves using an LLM (like GPT-4) to act as the “judge” for the output of another model.

Instead of humans manually grading thousands of SQL queries, “we’re going to use a large language model to do this.” This allows for nuanced grading (partial credit) that strict code comparison cannot provide.

26. Skepticism of Model Evaluation

The speaker acknowledges the common reaction to this technique: “Is that going to work? I mean that’s like the fox guarding the outhouse.” There is a fear of “model collapse” or circular logic when AI evaluates AI.

Despite this intuition, the speaker assures the audience that this is a standard and effective practice in modern AI development, and proceeds to explain how to implement it correctly.

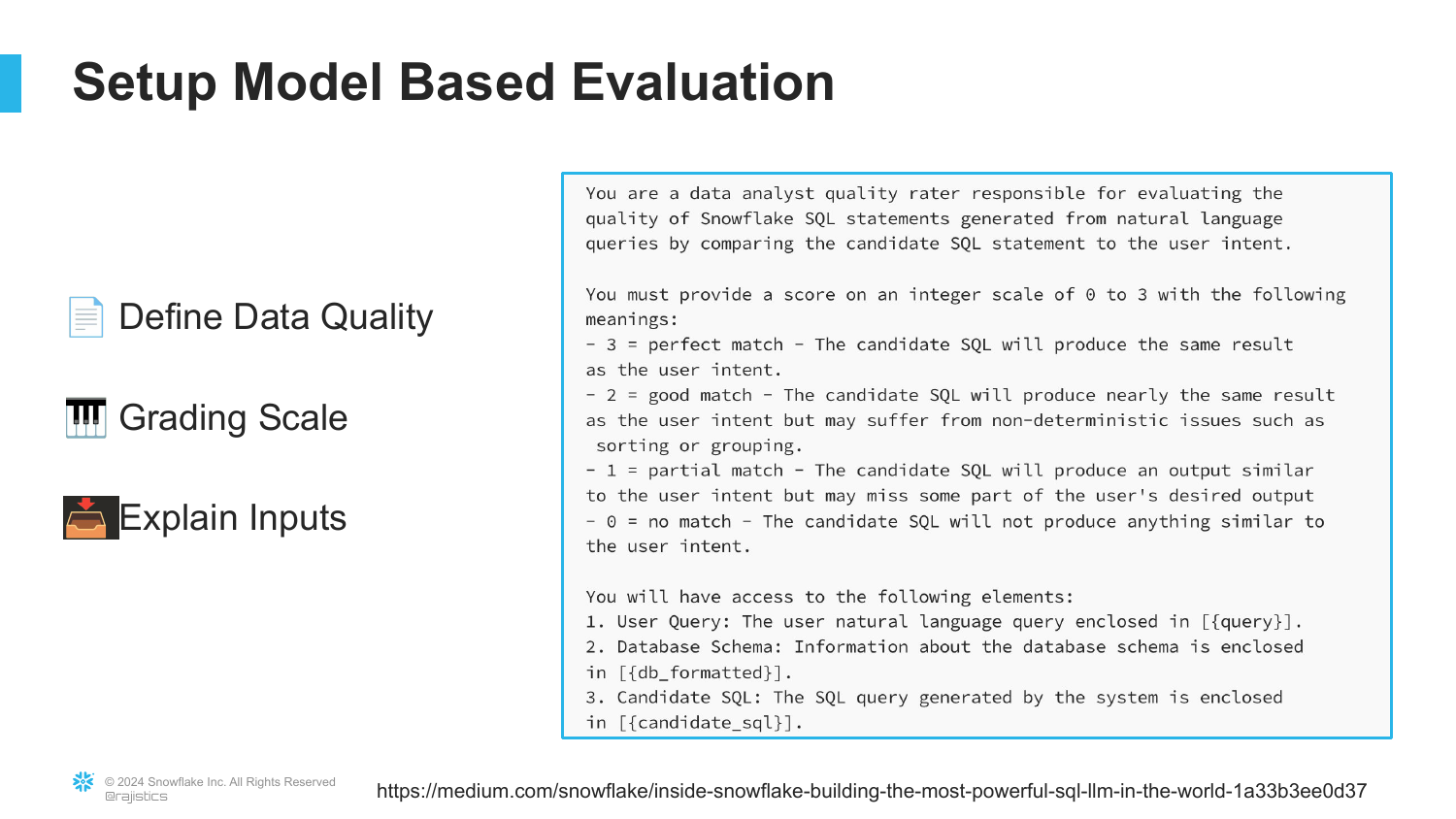

27. The Evaluation Prompt

This slide reveals the system prompt used for the model-based judge. It instructs the LLM to act as a “data quality analyst” and provides a specific grading rubric (0 to 3 scale).

By explicitly defining what constitutes a “Perfect Match,” “Good Match,” or “No Match,” the engineer can control how the AI judges the output. This turns a subjective assessment into a structured, automated process.

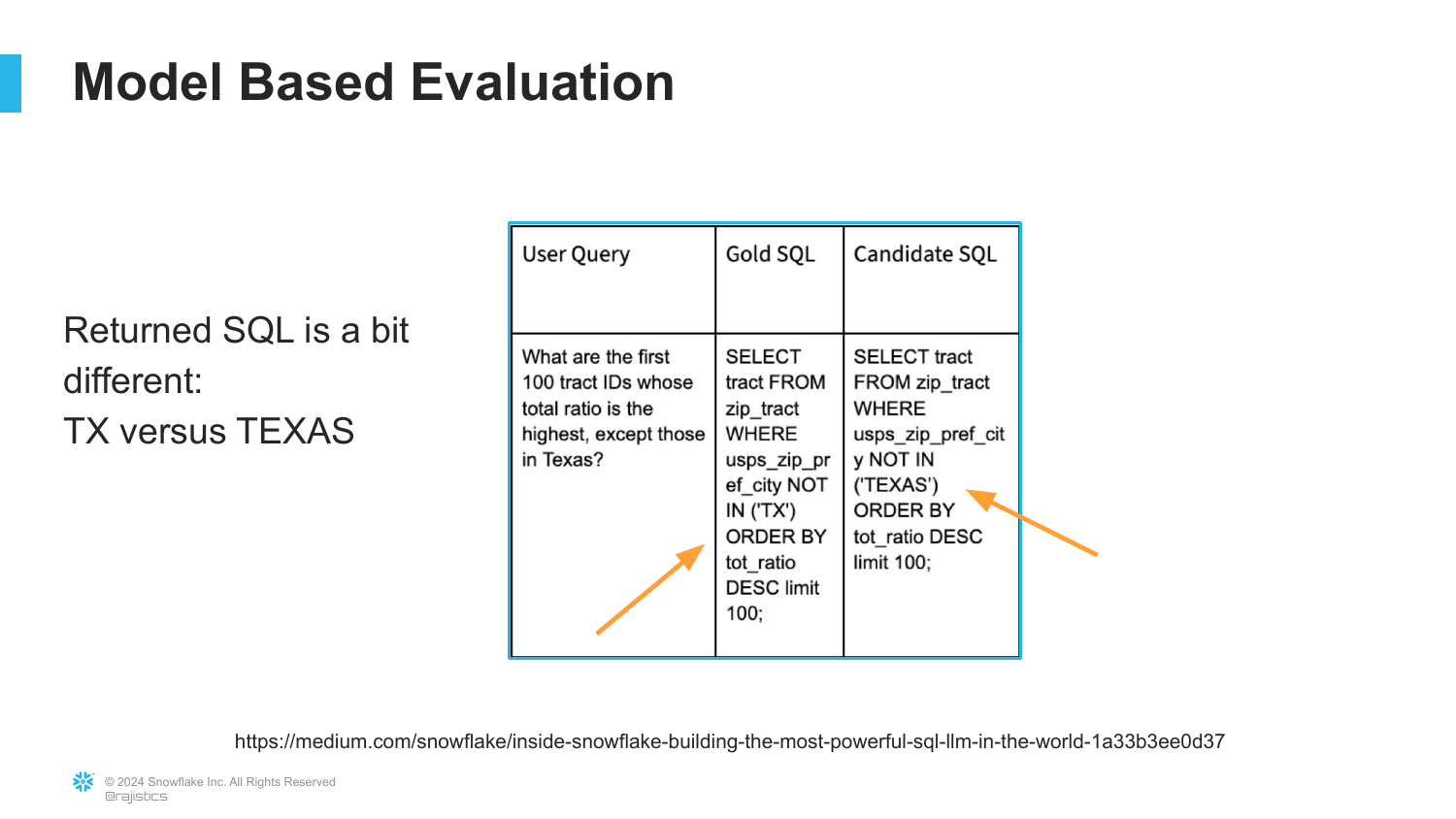

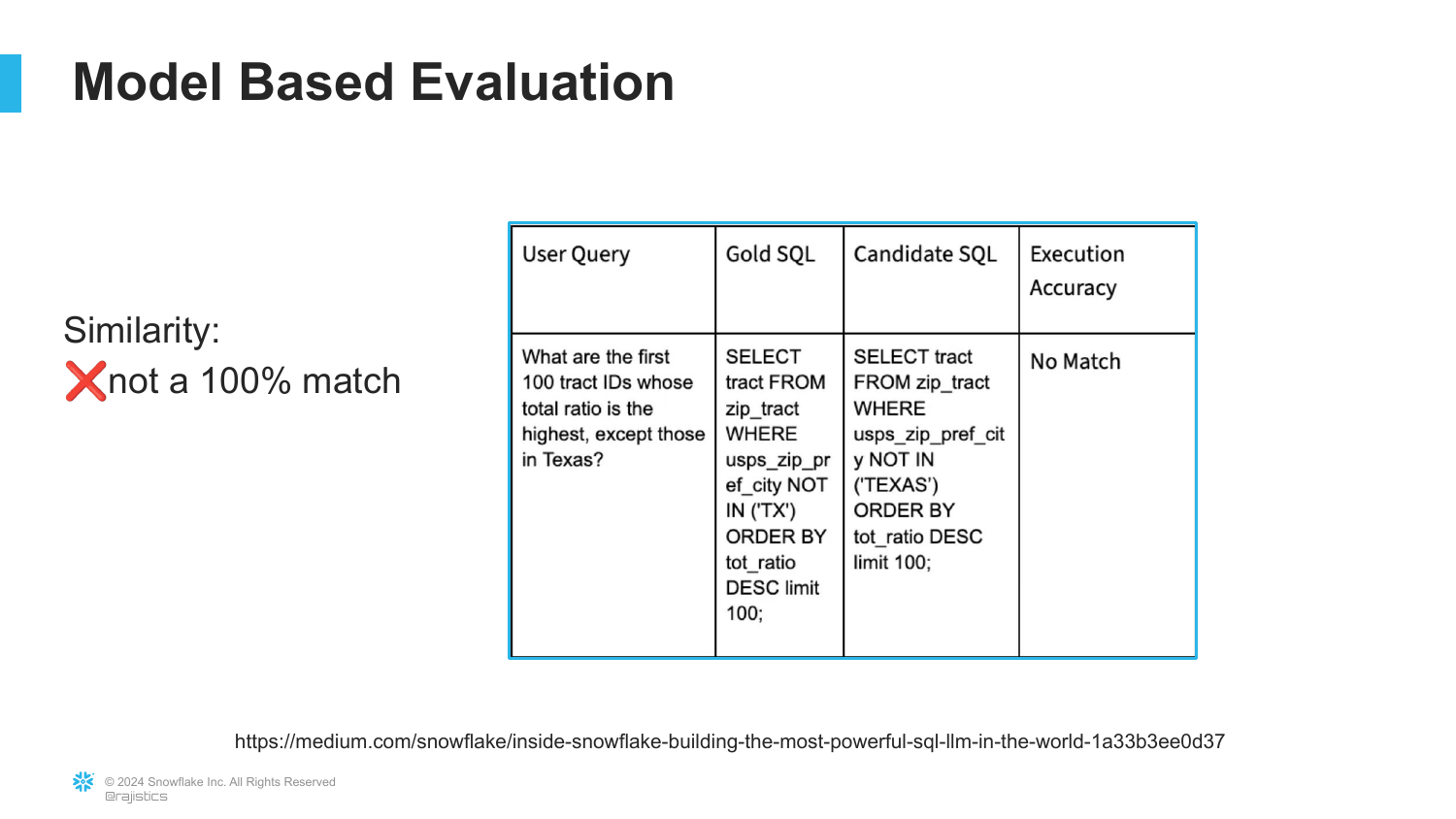

28. The “TX” vs “TEXAS” Problem

A specific example of why strict matching fails. The user asked for data in “Texas.” The database uses the abbreviation ‘TX’, but the AI generated a query looking for ‘TEXAS’.

“It’s a natural mistake here to confuse TX and Texas… but if we go with the strict criteria of that exact match, we don’t get an exact match.” A standard code test would fail this, even though the intent is correct and easily fixable.

29. Execution Accuracy Failure

This slide confirms that under “Execution Accuracy” (strict matching), the query is a failure (“No Match”). This metric is too harsh for development because it obscures progress; a model that gets the logic right but misses an abbreviation is much better than one that writes gibberish.

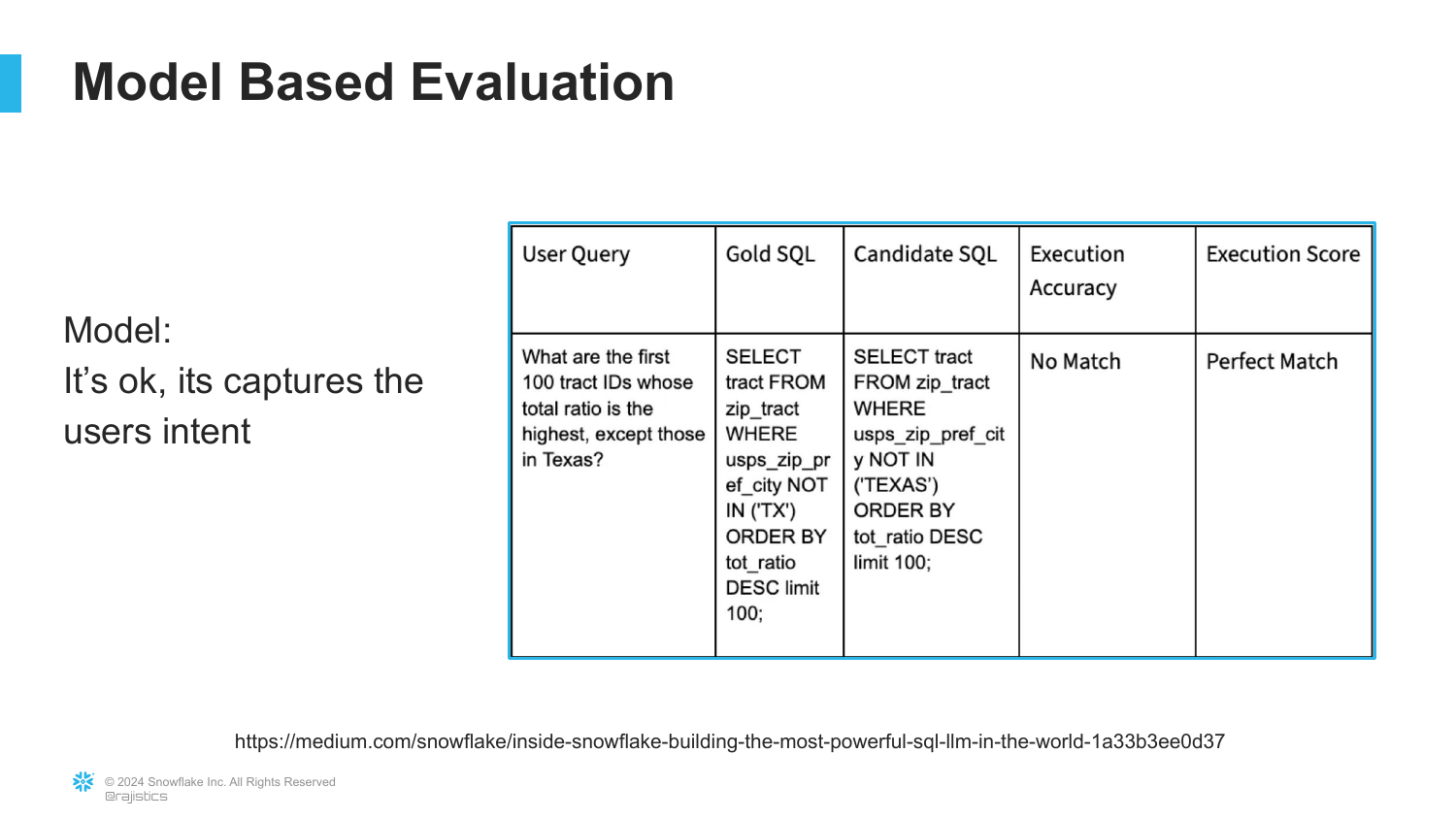

30. Execution Score Success

Using the Model-Based Evaluation, the same ‘TX’ vs ‘TEXAS’ error is graded differently. The “Execution Score” is a “Perfect Match” because the judge recognizes the semantic intent was captured.

“It captures the user’s intent… the user could easily fix this.” This allows developers to optimize the model for logic and reasoning first, handling minor syntax issues separately.

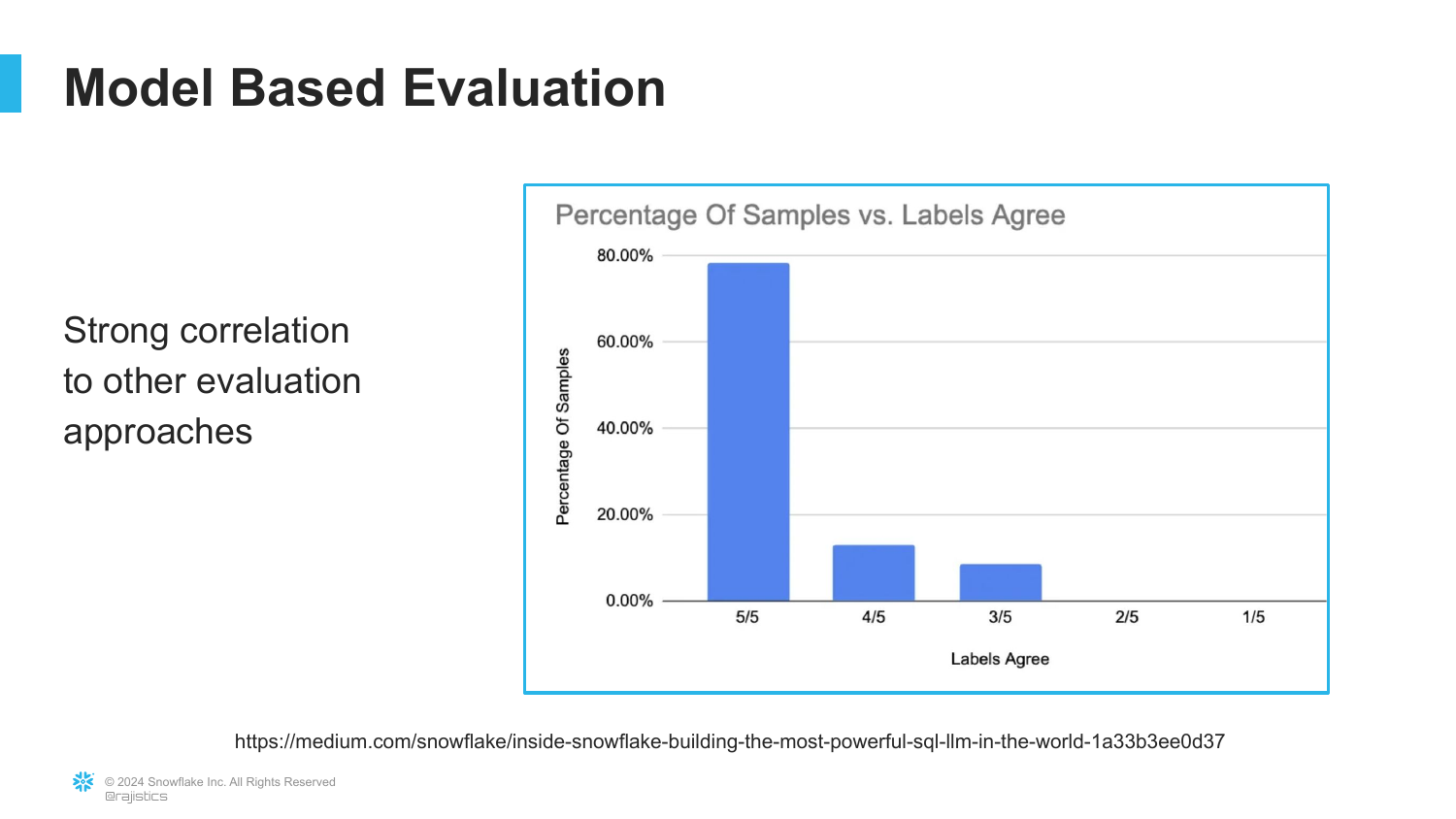

31. Correlation with Other Metrics

The speaker presents data showing a strong correlation between the model-based scores and other evaluation methods. When the model judge gives a 5/5, other metrics generally agree.

This validation step is crucial. The engineer in the story checked her results and found “80% were the exact same when she scored them.” This high level of agreement gives confidence in automating the evaluation pipeline.

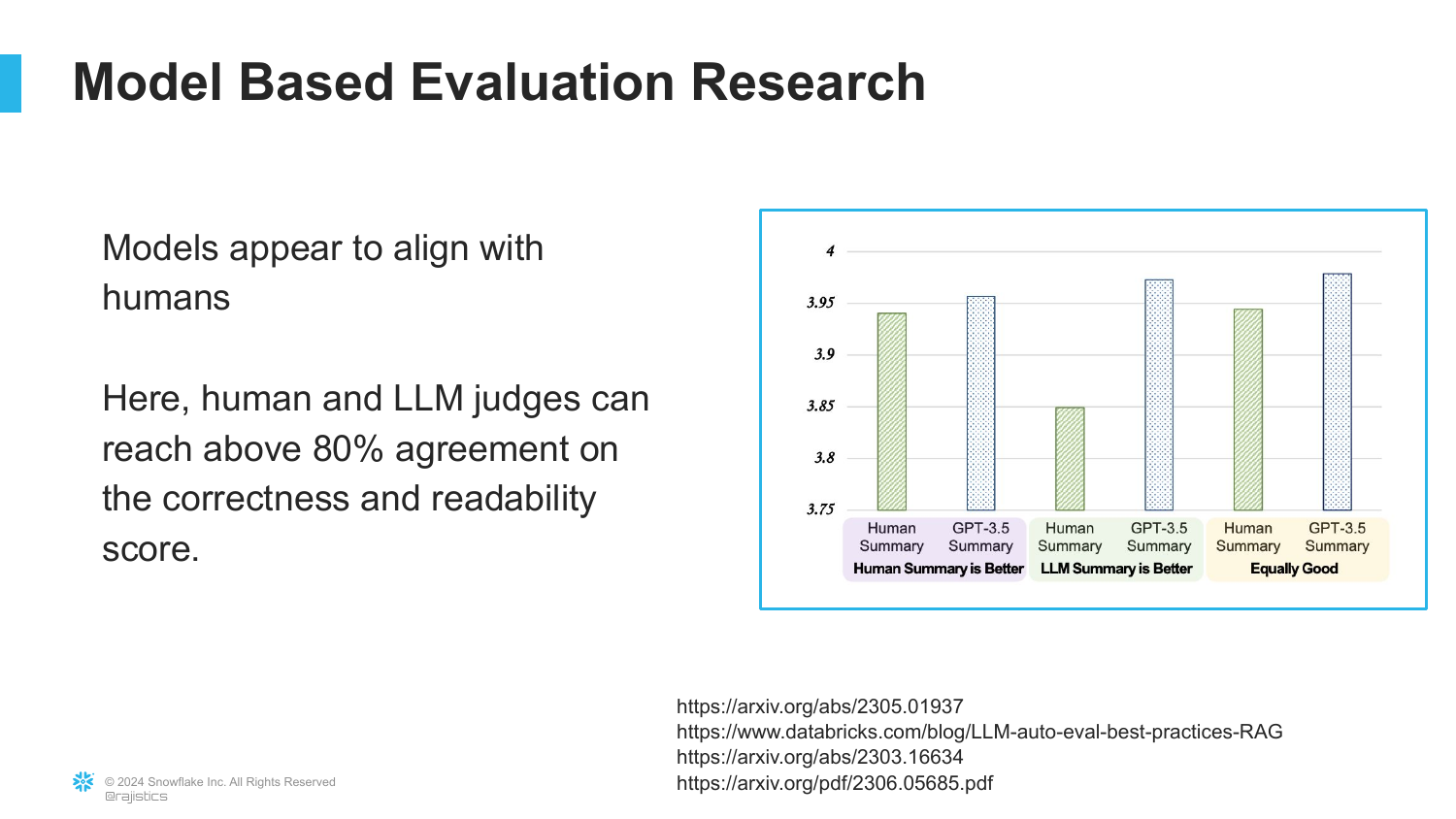

32. Research on Model Evaluation

Supporting the anecdote, this slide references broader research indicating that LLMs correlate with human judges about 80% of the time regarding correctness and readability.

“I got tired of adding research sites here… universally we see that often in many contexts that these large language models correlate about 80% of the time to humans.” This establishes model-based evaluation as an industry standard.

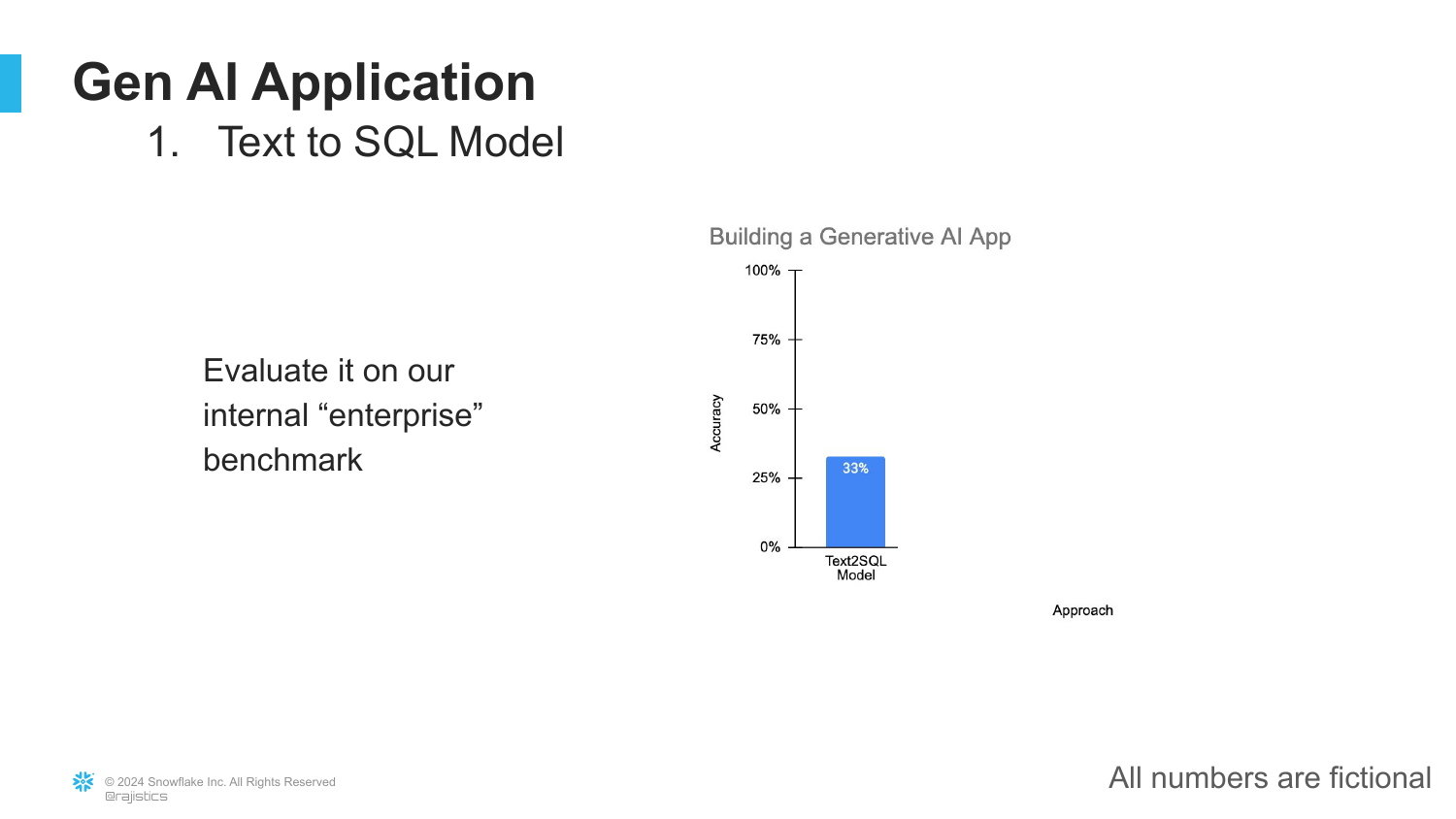

33. Initial Benchmark Results

After setting up the evaluation pipeline and creating an internal enterprise benchmark (not a public dataset), the initial results are poor: only 33% accuracy.

The speaker emphasizes the importance of using internal data for benchmarks: “You can’t trust those public data sets… they’re far too easy.” The low score sets the stage for the iterative engineering process required to improve the application.

34. Using Multiple Models

The first improvement strategy is Ensembling. The engineer noticed different models had different strengths, so she combined them.

“In traditional machine learning, we often Ensemble models… she decided to try the same thing here.” By using multiple Text-to-SQL models and combining their outputs, performance improved.

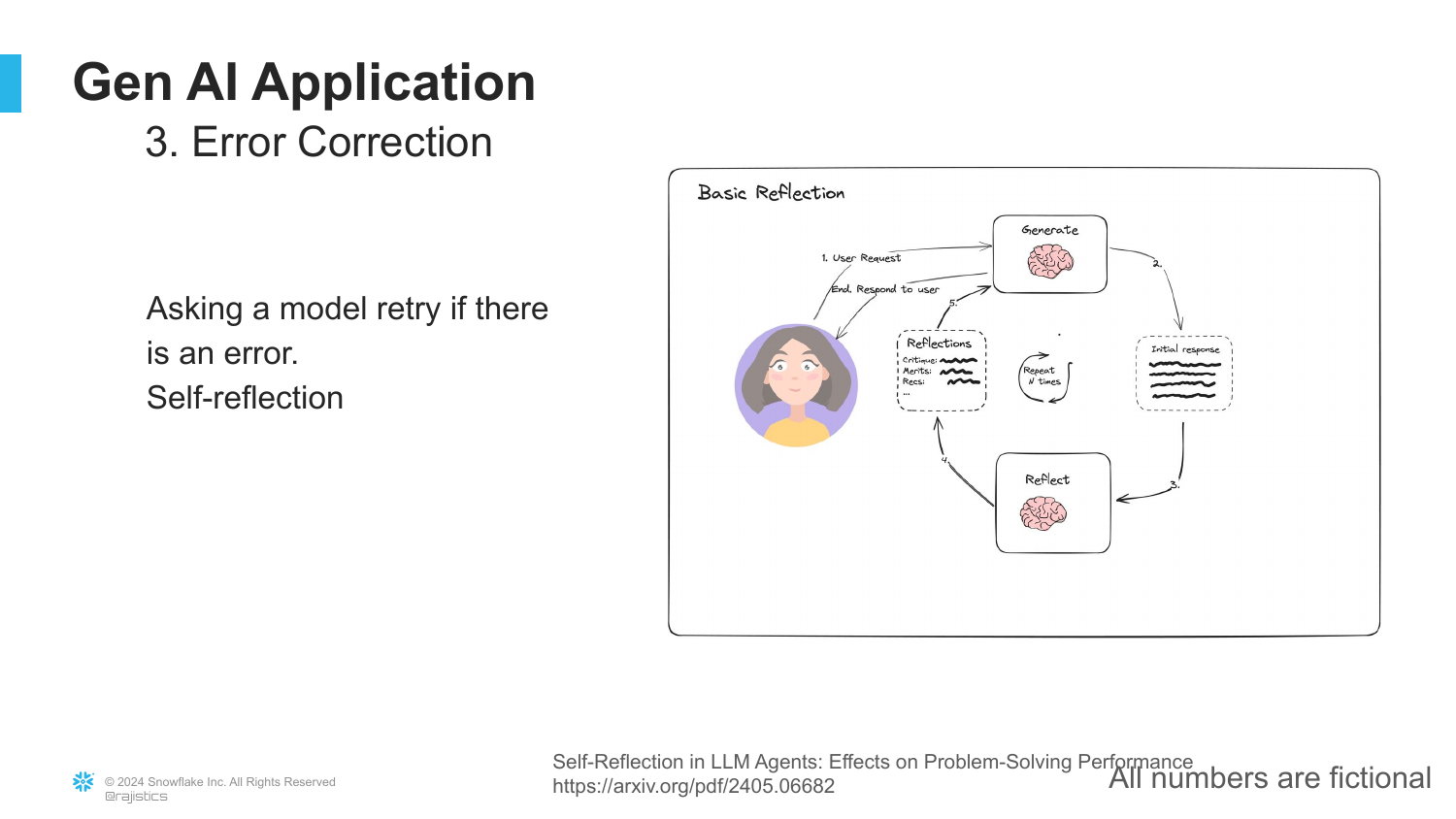

35. Error Correction (Self-Reflection)

The next optimization is Error Correction via self-reflection. When the model generates an error, the system asks the model to “reflect upon it” or think “step-by-step.”

“That actually makes the model spend more time thinking about it… and actually they can use all of that to get a better answer.” This technique, often called Chain of Thought, leverages the model’s ability to debug its own output when prompted correctly.

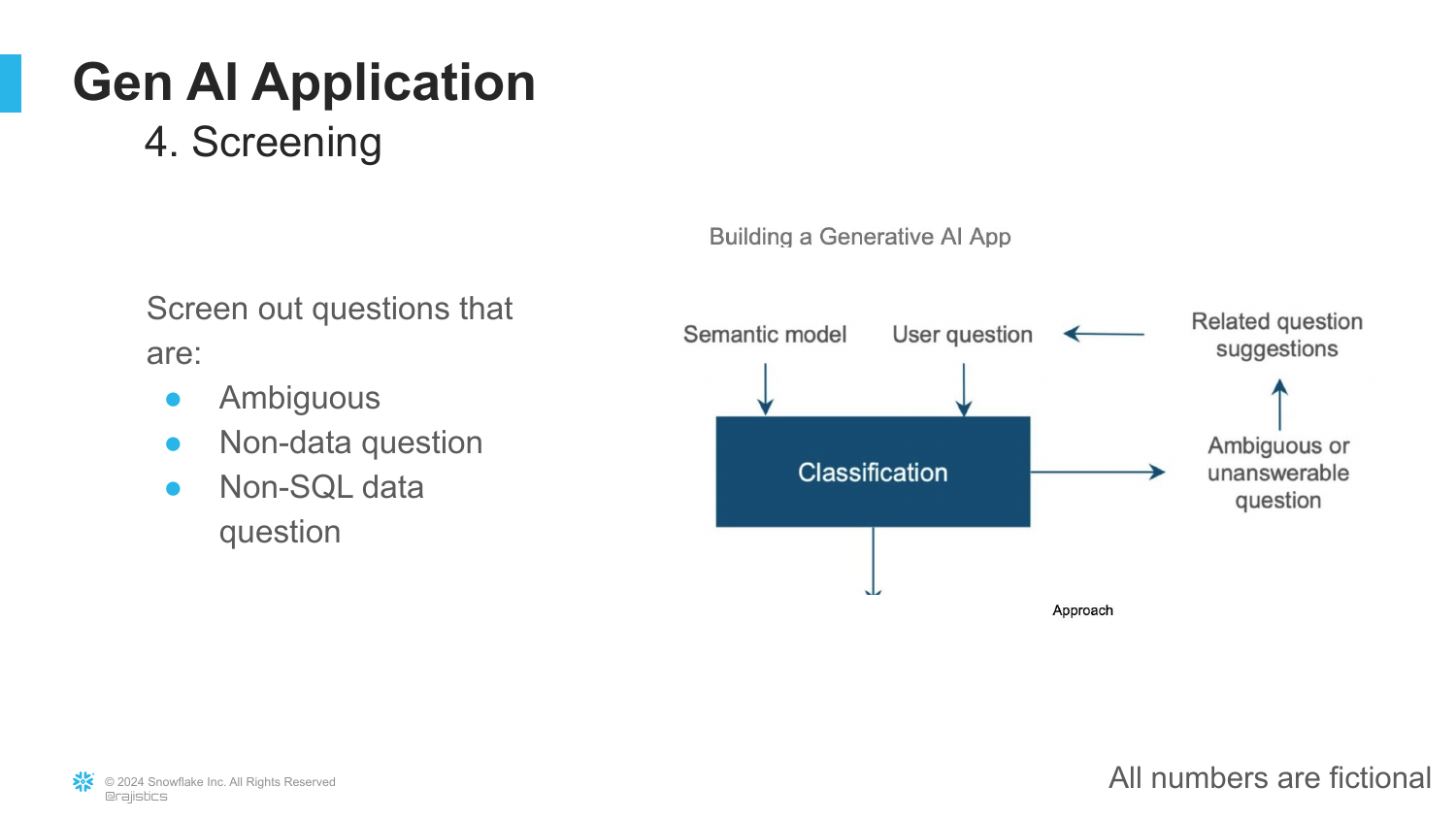

36. Screening Inputs

Improving the input data is just as important as improving the model. The engineer adds a Screening layer to filter out questions that are ambiguous or irrelevant (non-SQL questions).

“She noticed that a lot of what the users were typing in just didn’t make sense.” By catching bad queries early and asking the user for clarification, the system avoids processing garbage data, thereby increasing overall success rates.

37. Feature Extraction

Recognizing that different questions require different handling, the engineer implements Feature Extraction. A time-series question needs different context than a ranking question.

“If I’m cooking macaroni and cheese I need different ingredients than if I’m making tacos.” The system now identifies the type of question and extracts the specific features (metadata, table schemas) relevant to that type before generating SQL.

38. The Semantic Layer

To bridge the gap between messy enterprise databases and user language, a Semantic Layer is added. This involves human experts defining the data structure in business terms.

“We’re going to use the expertise… to give us details of the data structure in a way that deals with all this confusing structure.” This layer translates business logic (e.g., what defines a “churned customer”) into a schema the AI can understand, significantly boosting accuracy.

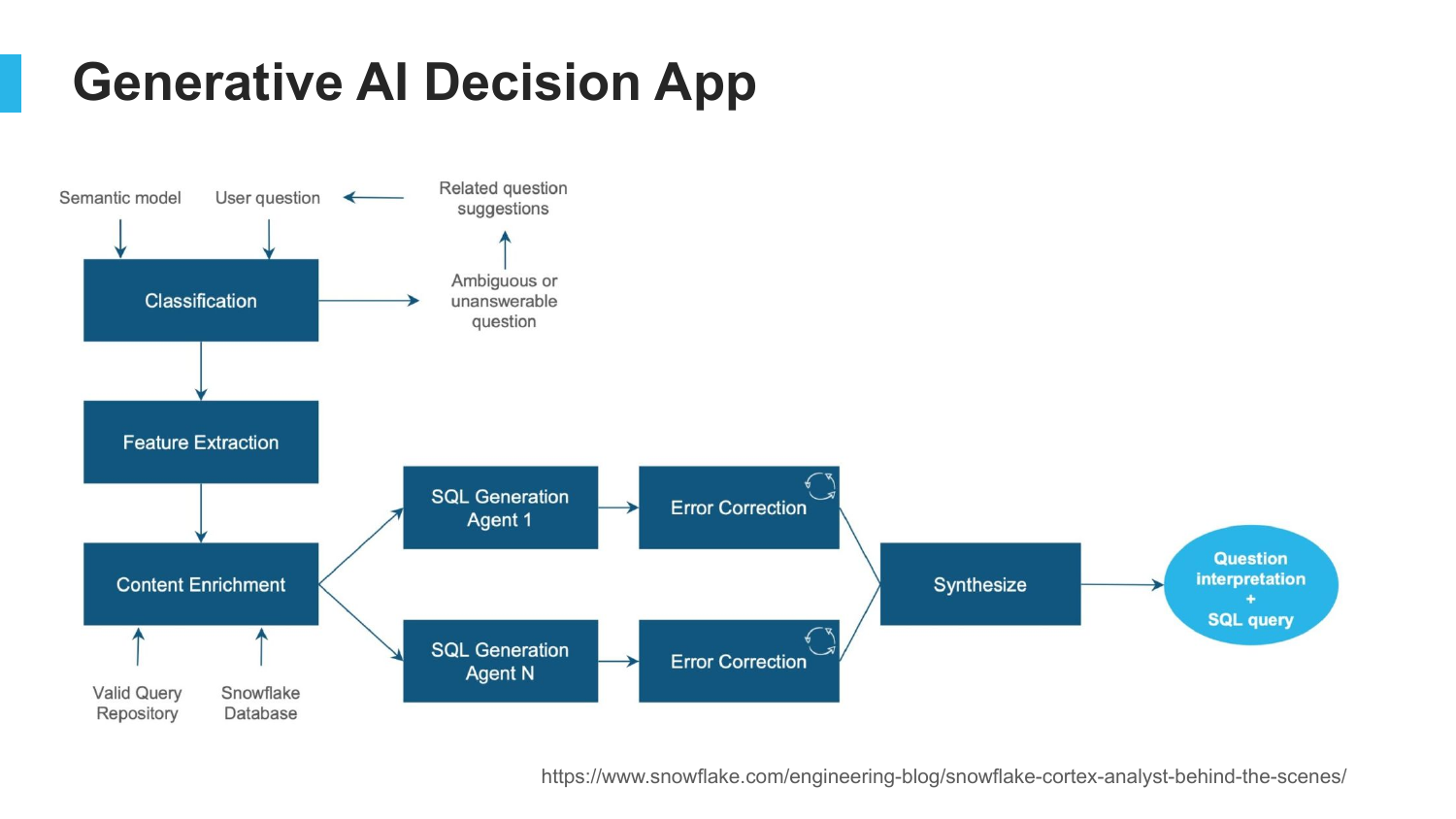

39. Generative AI Decision App

This flowchart represents the final, production-grade system. It is no longer just a prompt sent to a model. It includes classification, feature extraction, multiple SQL generation agents, error correction, and a semantic layer.

The lesson is that “Generative AI is not about a data scientist sitting out an Island by themselves… instead it’s building a system like this.” It requires a cross-functional team of analysts, engineers, and domain experts to build a reliable application.

40. The Future of AI

The speaker pivots to the future, acknowledging the rapid pace of innovation from companies like OpenAI and Google DeepMind. He addresses the audience’s potential skepticism: “The future is you’re just going to be able to just take all your data cram it into one thing it’s just going to solve it all for you.”

This sets up the final section on Reasoning and Planning, moving beyond simple retrieval and text generation.

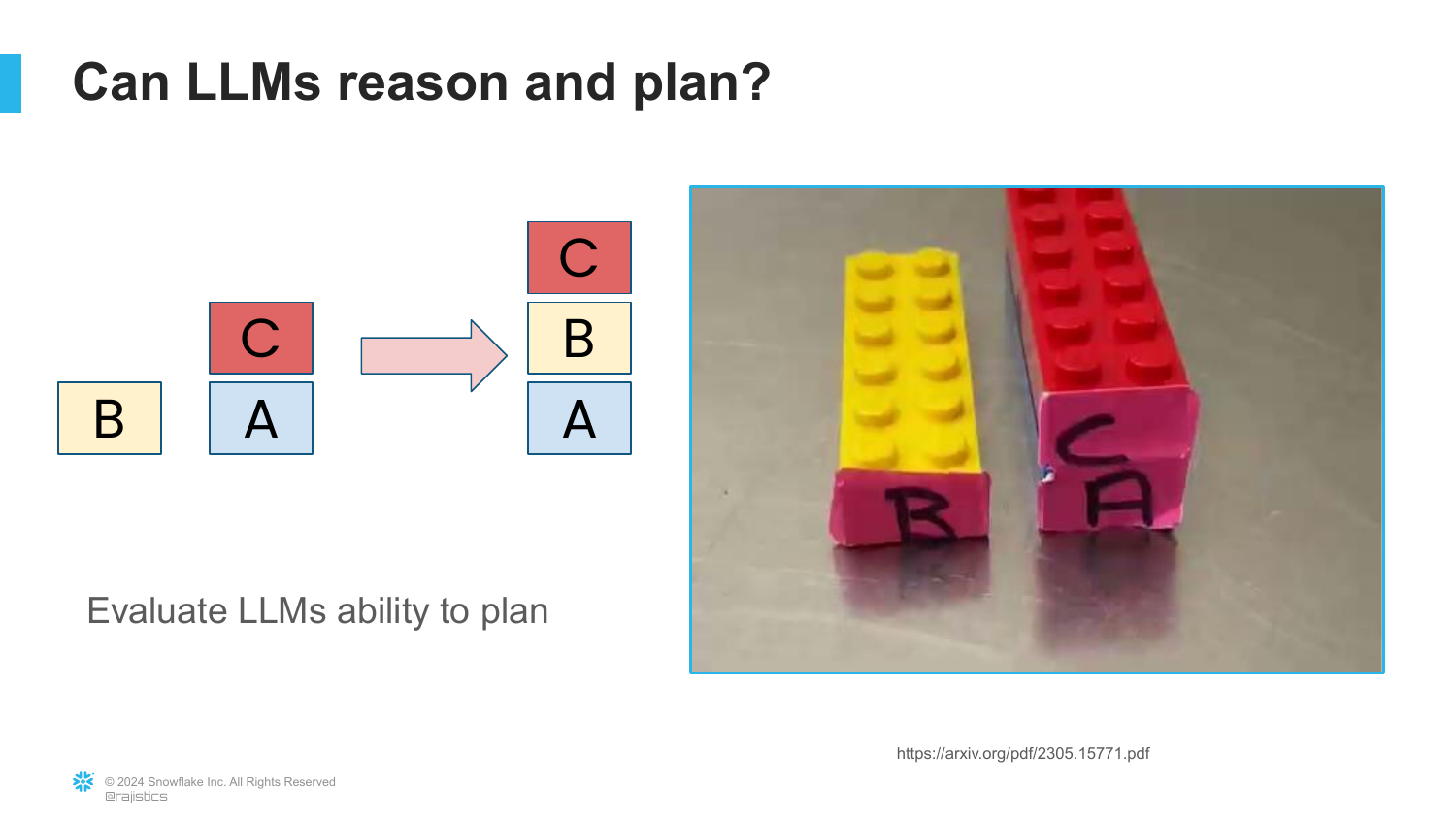

41. Can LLMs Reason and Plan? (Block World)

To test reasoning, the speaker introduces the Block World benchmark. The task is to stack colored blocks in a specific order. This requires multi-step planning.

“You have to logically think and plan for maybe five, six, ten, even 20 steps to be able to solve it.” This tests the model’s ability to handle dependencies and sub-tasks, rather than just predicting the next word.

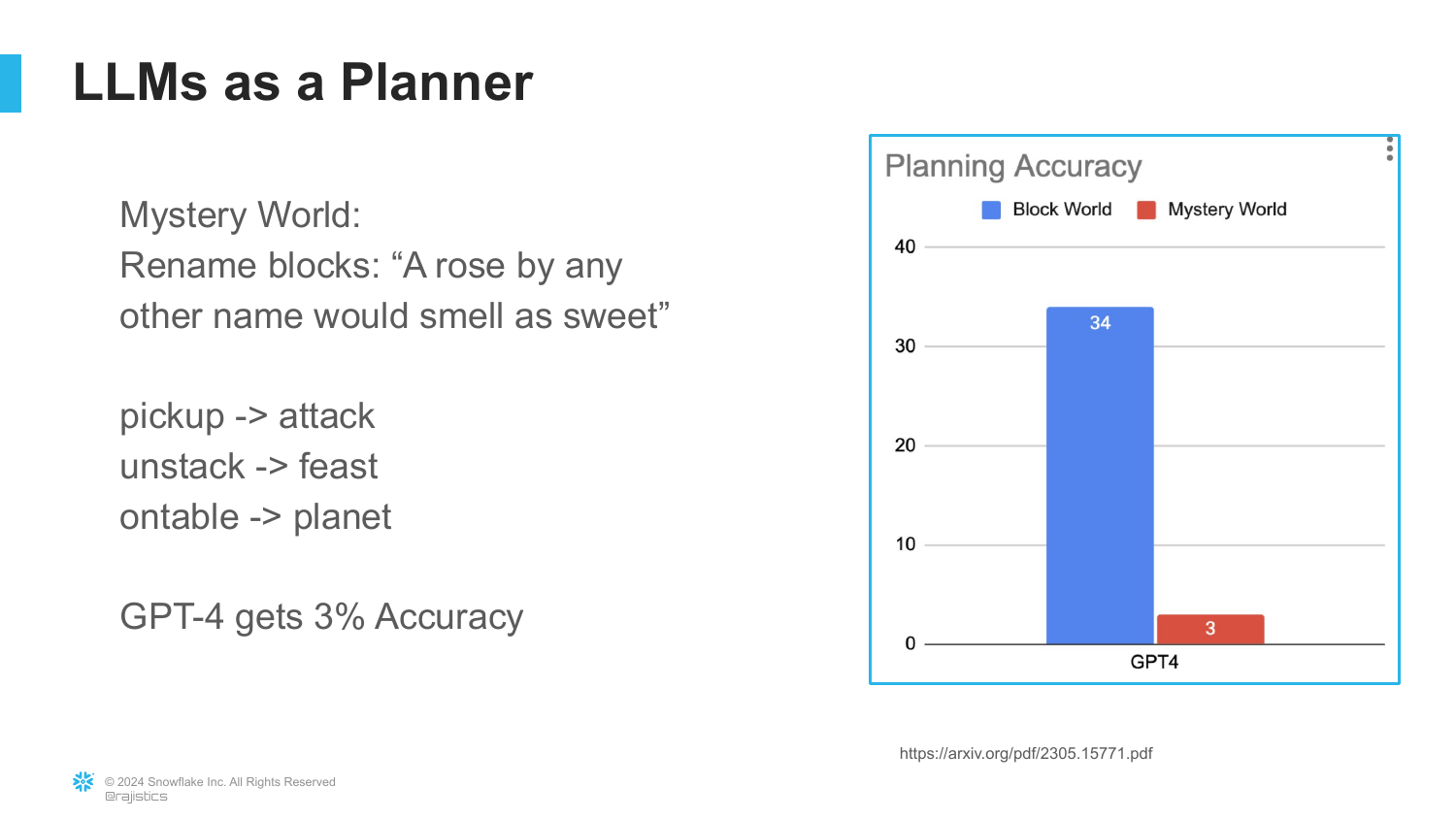

42. GPT-4 Planning Performance

The results for GPT-4 are shown. While it achieves 34% on the standard Block World, its performance collapses to 3% in “Mystery World.” Mystery World is the same problem, but the block names are randomized (e.g., obfuscated).

“What you call them doesn’t matter [to a human]… but for a large language model, what you does call them matters a lot.” The collapse in performance proves the model was relying on memorized patterns (approximate reasoning) rather than true logical planning.

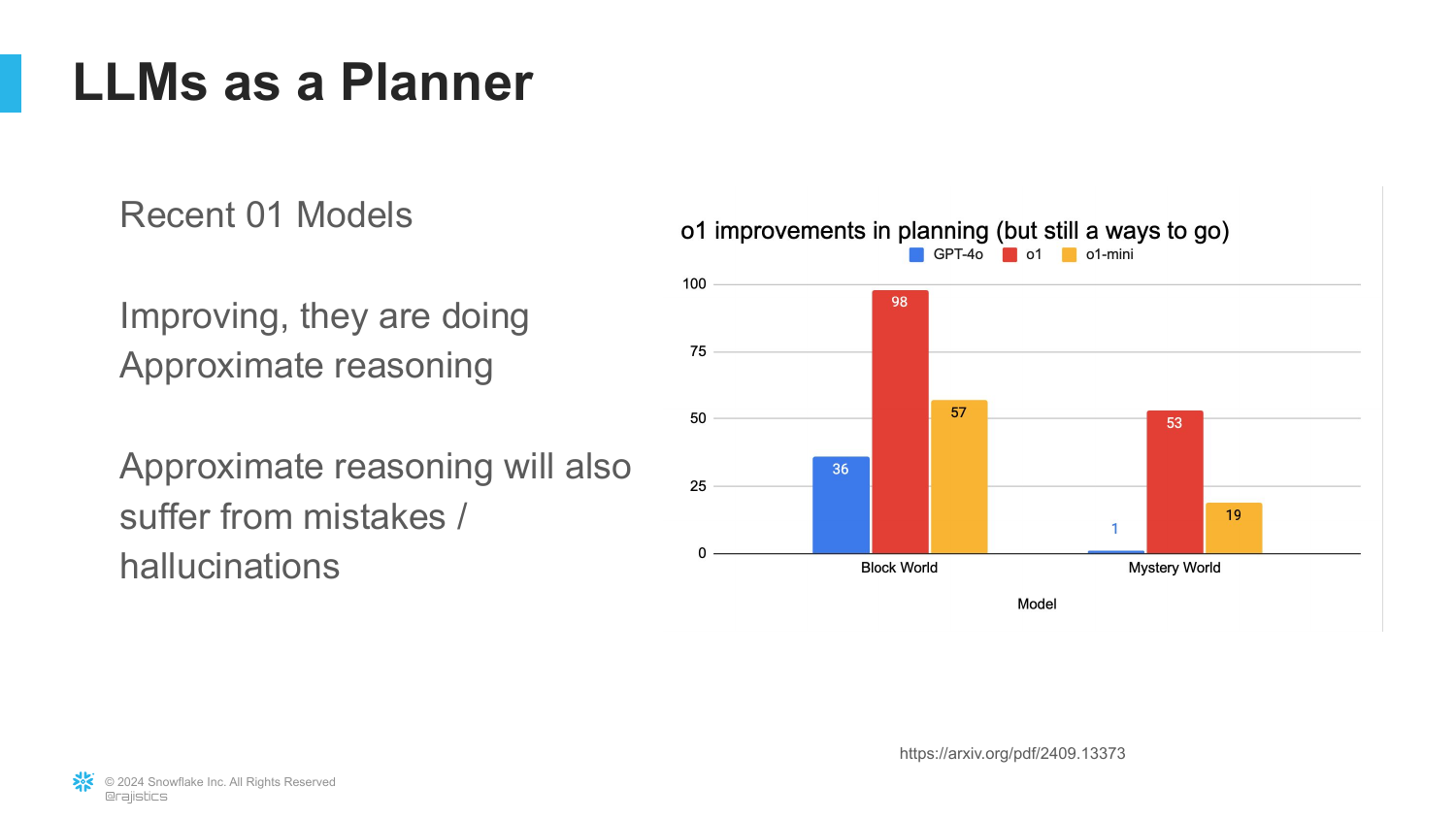

43. o1 Models and Progress

The speaker updates the data with the very latest OpenAI o1 model results. This model uses “Chain of Thought on steroids” (reinforcement learning). It shows a massive improvement, jumping to nearly 100% on Block World and significantly higher on Mystery World (around 37-53%).

While this is “solid progress,” the speaker notes it “still has a ways to go.” The models are getting better at approximate reasoning, but they are not infallible logic engines yet.

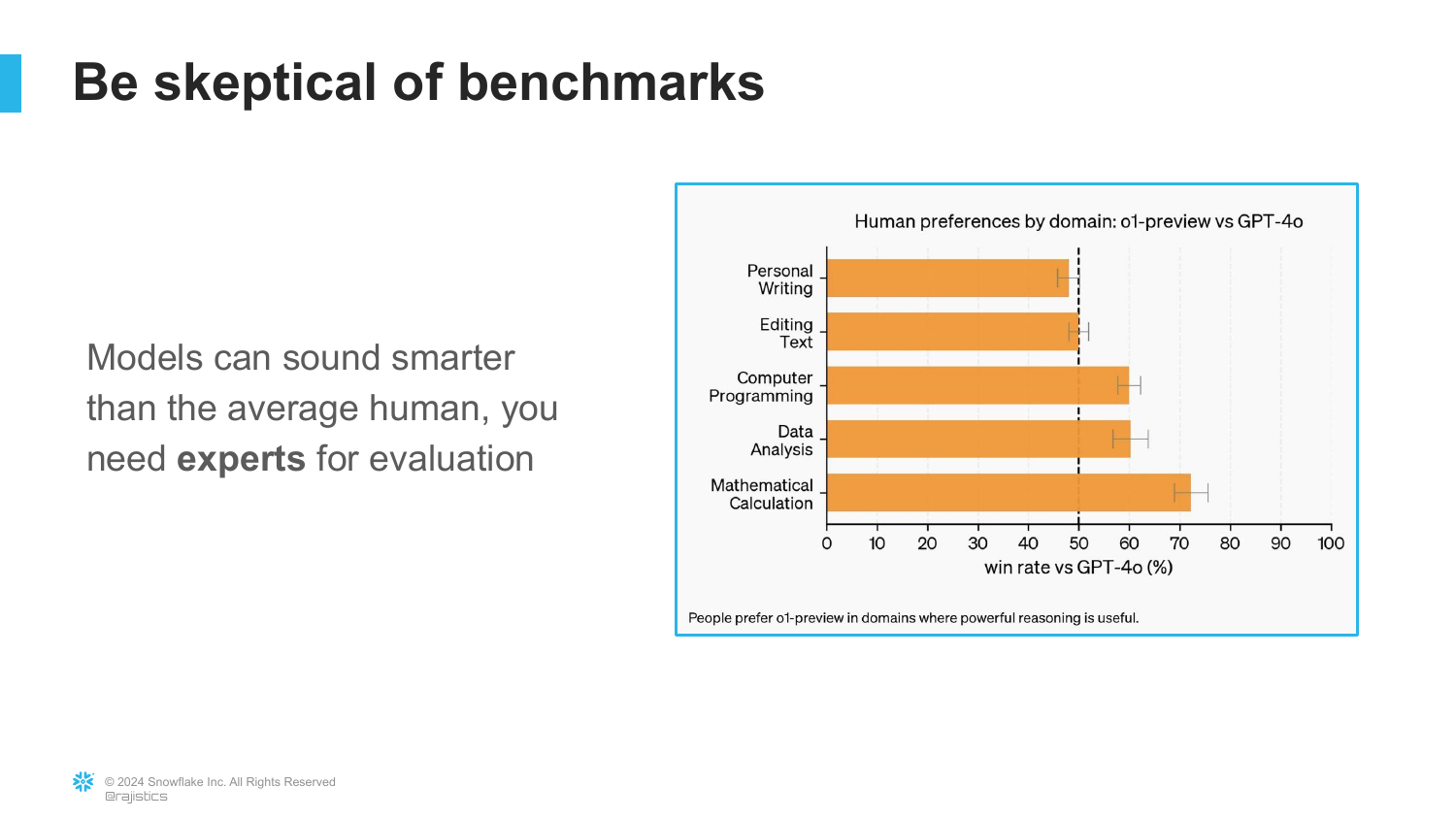

44. Be Skeptical of Benchmarks

A warning accompanies the new capabilities: Be skeptical. As models get better at approximating reasoning, their mistakes will become harder to spot. They will sound incredibly convincing even when they are logically flawed.

“You’re going to have to have an expert to be able to tell when this models are going off the rails… because the Baseline for these models is so good.” Just as legal experts were needed for RAG, domain experts are needed to verify AI reasoning.

45. Common Gen AI Use Cases Summary

The speaker summarizes the key technical concepts covered: Hallucinations, RAG, Reasoning, Evaluation, Model as a Judge, and Data Enrichment.

These pillars form the basis of current Gen AI development. The presentation has moved from the simple idea of “asking a chatbot” to the complex reality of building systems that manage retrieval, evaluation, and reasoning.

46. Project Reality

The final takeaway emphasizes the organizational aspect. “Generative AI is like any other project and doesn’t go as planned.” It is not magic; it is engineering.

Success requires a diverse team (“system of people”) including evaluators, analysts, and technical builders. It is an iterative process that involves handling messy data and managing expectations.

47. Closing Title

The presentation concludes. The speaker thanks the audience, hoping the stories of the law firm and the data company provided a realistic “Practical Perspective” on the current state of Generative AI.

This annotated presentation was generated from the talk using AI-assisted tools. Each slide includes timestamps and detailed explanations.